(Note: In quoting historic documents, I have not attempted to modernise their Anglicised spelling and usage of Māori words, offensive as some of these things may seem today. The English language of the time, loaded as it was with racist terms and concepts – like ‘half-caste’ – and the mangling of the Māori language, were very much part of the problem that the workers in this story had to navigate, and need to be seen in their original form in order to understand and appreciate the situation.)

The six-month-long strike at the Waihi gold mine in 1912 was the longest and most hard-fought class battle fought on New Zealand soil to that date. It pitted the Waihi Miners’ Union and the wider class-struggle-led union movement of which it was part, the “Red” Federation of Labour, against the gold mine owners, the small business people of Waihi, the employers organisations nationwide, the capitalist press, the police and justice systems, the government, the pro-Arbitration majority of the trade unions, a scab union set up by the bosses, and towards the end, employer-organised thugs and strikebreakers. Among that last category were a significant number of Māori.

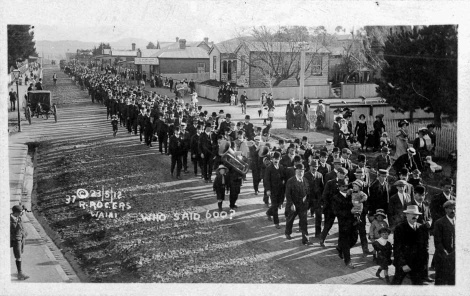

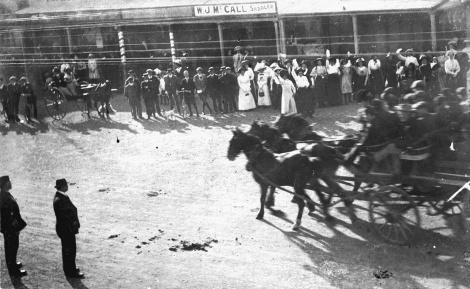

Striking miners march through Waihi 23 May 1912, about a week after beginning of the strike. Photo: Waihi Arts Centre and Museum

A permanent, hereditary working class had only existed in New Zealand for two decades at the time; the Waihi strikers were fighting on new and unfamiliar territory. It was, for example, the first time workers in New Zealand had waged a serious fight against a scab union: understanding the nature of the beast, and educating other workers about it, was no easy task. (The only prior experience of a scab union was six months earlier in Auckland, where a breakaway union was formed from amongst Auckland city labourers at the instigation of the Grey Lynn Town Clerk. That new union quickly registered under the Arbitration Act, and successfully stymied efforts to organise a fighting union of labourers in the city.)

Waihi was also the first time a concerted effort had been made by the capitalists to recruit Māori as scabs in a labour dispute, and so it was not immediately clear how to respond to this challenge.

Pukewa hill, on which the Waihi gold mine was established, had been wāhi tapu belonging to the Ngāti Hako hapū, one of the Tainui tribes of the Hauraki plains. The first gold prospectors who began tunnelling into the quartz outcrop in 1878 quickly discovered this when they were confronted with a group of Māori angrily protesting their desecration of an ancient burial site. [See Roche, The Red and the Gold, pp12-14 for more detail].

Kahikatea forest at Purerora. Much of the Hauraki plains was covered with forests like these. Photo: Waikato Regional Council

Under Māori stewardship, the Hauraki plains had been a bountiful wetland. Its rivers, harakeke marshes, and forests of giant kahikatea (up to 60 metres tall and with trunks 2 metres in diameter), abundant with kererū, fish, and eels, supported a large Māori population. Rivers were the highways of communication – the Waihou River (named the Thames River by European explorer James Cook because of its resemblance to the great Thames River flowing through London) was navigable as far south as Matamata.

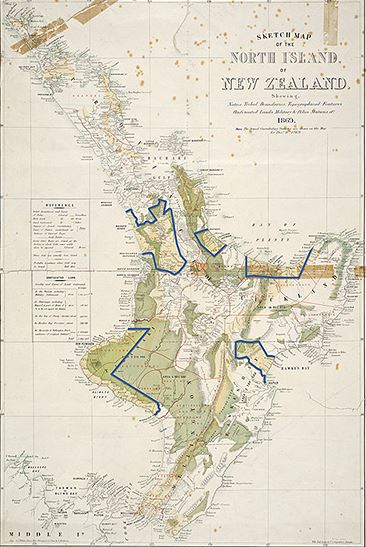

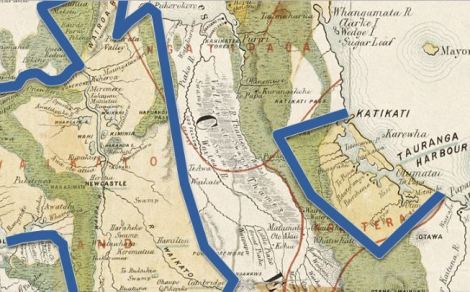

Blue lines show areas of Maori land confiscated by the government after the land wars of the mid-19th century Map: Auckland City Libraries – Tāmaki Pātaka Kōrero, Sir George Grey Special Collections Reference: NZ Map 471

Following the alienation of the land through raupatu [confiscation] and purchase after the land wars of the 1860s, the wetland was drained and its rich peat soils transformed into dairy farms for European settlers; the Waihou River silted up and became the filthy dairying-effluent-laden drain it is today.

The great kahikatea forests were cut down; the kahikatea timber was made into butter boxes – one of the greatest of the many acts of environmental devastation that accompanied European settlement. (See Ngā Uruora, the Groves of Life, by Geoff Park, for more on this).

Gang of labourers digging the drains on the Hauraki plains, early 1900s. Remnants of Kahikatea forest can be seen in the background. Photo: Ohinemuri Regional History Journal 55, September 2011

Māori landholdings were reduced to the less productive mānuka-scrub-covered hills to the east, and when gold was discovered there, they were lost too. Allotment of European farms and settlement and the draining of the wetlands had begun not long before the time of the Waihi strike.

Nga Uruora, by Geoff Park, describes the destruction of the lowland forests.

In that period Māori had little reason to feel common cause with the labour movement. The confiscations of their best land (and further purchases under duress) had not only destroyed their commercial farming which had supplied food to the urban colonists, it had also left the industries Māori had established, including flour-mills and coastal shipping, in ruins. Māori were pushed to a bare subsistence on the rural margins, excluded from access to the cheap credit available to settler-farmers and thus from the means to develop these remaining lands on an equal basis. They were thereby also excluded from commercial farming of wool, meat, and dairy products for export.

Maori land ownership in North Island. Note the loss of the Hauraki plains and along the Waihou valley and Kaimai range between 1890 and 1910. Graphic: Creative Commons Source: Claudia Orange, Illustrated history of the Treaty of Waitangi.

The labour movement itself had only recently emerged from this colonial enterprise; during its first two decades of existence it was locked in close political alliance with the Liberal Party government, which ruled from 1890 to 1912 and was responsible for the most rapid phase of alienation of Māori land. (If the pace of alienation of Māori land slowed after 1912, it was only because all the best land had already been sold).

It would not be until after the Second World War that a mass migration of Māori to urban areas would begin. In 1912 Māori were excluded from the urban trades, and therefore also from the union movement. The years around the turn of the century were the nadir of the Māori nation – many were living in conditions of extreme poverty and ill-health. They remained a significant component of the working class in semi-rural industries such as flax-milling, as well as in such work as construction of roads and farm buildings and draining the swamps, and as shearers and farm labourers; however these rural workers were mostly beyond the reach of the unions, at least until the rise of the Red Feds from 1906. There was, therefore, a significant unemployed and under-employed ‘surplus population’ in the Māori communities.

For the gold miners at Waihi, there was much at stake in the strike that began in May 1912. They were defending the union which had won significant improvements in safety and health conditions in the mine, and had forced the bosses to end the divisive system of competitive contracting that pitted miner against miner. For four months, the Waihi strikers succeeded in keeping the mine closed and the town quiet, while the mine owners made no move to open it with scabs. (The bosses were hoping to starve the miners back to work, and their tactic depended on maintaining the pretence that the strike was a dispute between two groups of workers in which the owners were innocent bystanders.) When the union succeeded in raising funds to support the strikers and the starvation strategy had clearly failed, the mine bosses and their government moved to incite violent incidents by means of police provocations and arrests. By October, some 45 strikers had been hauled before the courts and carted off to prison in Auckland, including the entire local union leadership. More were arrested over the next few weeks until there were more than 70 altogether. On October 2, the gold mining company announced the re-opening of the mine with scabs.

Pickets and their families jeer at strikebreakers being carried to the mine on horse-drawn brakes. Photo: Waihi Arts Centre and Museum

Only a small number of strikebreakers appeared for work on that morning, while a large number of Federationist miners and their families turned out to denounce them as scabs and traitors to their class. The strike-breakers included a group of about twenty who had already been working the battery at Waikino for a week or so. Federation leader Robert Semple had described this early strike-breaking effort in an interview in the NZ Truth 28 September. “Just now, at Waikino, they had got a few old men and overgrown Maori boys on the job, and in ordinary circumstances the company wouldn’t give these ancients and boys a job. There was no chance of the miners turning to. No miners could be got to scab. A few head of stampers might be set going to crush the quartz on hand, but after a few days there would be nothing left to feed them. The miners and their leaders might be gaoled, but there was no chance of the strike fizzling out, as the daily papers declared.”

If the reference to ‘overgrown Maori boys’ had a whiff of racist condescension about it, Semple was not alone. Other Federation leaders expressed their contempt of the strikebreakers in such terms. Peter Fraser, speaking in the name of the Federation, telegrammed to the press from Waihi about the first day of the scab operation, “Great success here. Only four miners by occupation, three of them employed surface, returned [to work]. Twenty others drafted from Waikino, mostly Maori boys and derelicts. Great enthusiasm. Crowds of workers and their wives everywhere.”

The Maoriland Worker, voice of the Federation of Labour, described the first day’s strikebreakers as “young lads, half-caste Maori boys and a couple of gray-whiskered derelicts of capitalism. As they marched past the crowd at the comer of Seddon and Barry streets they looked like felons. With downcast heads and pallid faces, they were indeed a sorry spectacle.”

The Maoriland Worker at least recognised the dire threat to working class interests posed by the efforts to recruit Māori strikers – albeit that their statement also reveals a noticeable blindness regarding the status of Māori. An editorial on the push to break the strike reads, “Beset by every temptation, coaxed by every bribe, bullied and flattered, threatened and beslivered, this beacon union at Waihi stood its ground last week as bravely and as solidly as any known army of blood. Quite calmly and deliberately it can be claimed that nothing was left undone to try and break the Waihi Workers’ Union’s ranks and thus cause a stampede. The pressure brought to bear was enormous, ranging from intimidatory legal notifications to unprecedented lying by allegedly honourable pressmen, with a hundred both petty and powerful measures between. And of this union of 1200 and more not a quartette was found weak or treacherous! And of the miners on contract, not one contractor proved worm or renegade!…

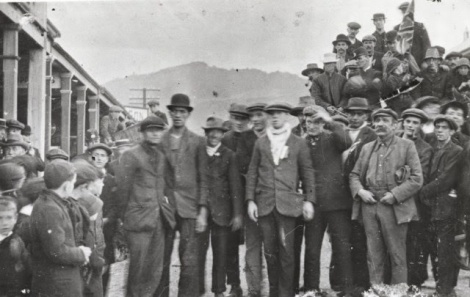

Strikebreakers at Waihi carrying the Union Jack, 1912, including a number who are clearly Māori. Photo: Waihi Arts Centre and Museum

“We feel impelled to make brief reference to the detestable entrapping of Maoris into bosses’ strike-breaking lackeys. We have hitherto rejoiced in the non-existence of the colour line in this country, and speak only because we are seriously concerned lest other days should know not Joseph [a Biblical reference to a story in Exodus, where a new king of Egypt who ‘knew not Joseph’ began systematically enslaving and oppressing the Jews]. Maoris have been duped and deceived into service as union-smasher.

“On this point, what are the parliamentary representatives of the Maori race doing that they should sit silently inactive while emissaries of the employers are travelling among the Maoris and by every possible device practically kidnapping some of them into scabbery? Have these parliamentary representatives no pride in the continued good name of their people that, they do not indignantly resent the tainting of them with the indelible tarnish of strikebreaking? Do they understand what it will mean racially if once the workers are made to regard the Maoris as potential industrial blacklegs?”

(One indication of where this could lead was an incident where a Māori travelling towards Paeroa near Waihi by train, with two pākehā companions, was assumed to be a strike-breaker by a Federationist travelling in the same carriage, and threatened with a pistol to his head. His pākehā companions were left unmolested. The case eventually led to a conviction of the Federationist.)

Māui Pōmare, MP for the Western Māori electorate, in 1916. Pōmare voted with the Reform government to keep the Waihi strikers in prison. Photo: S P Andrew Ltd Ref: 1/1-014581-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

The Māori Members of Parliament at this time were Āpirana Ngata, Te Rangi Hīroa, James Carroll and Taare Parata, all aligned with the Liberal Party, and Māui Pōmare, who was a minister without portfolio in the Reform government that took office in July 1912. On 1st November, as public pressure mounted against the unjust jailing of the 70 Waihi strikers, there was a parliamentary discussion and vote on releasing the strikers. James Carroll, Te Rangi Hīroa, Taare Parata favoured immediate release, Māui Pōmare voted with the majority to keep them in jail for a year. Āpirana Ngata’s vote is not recorded.

The number of strikebreakers slowly increased each day. Economic pressures continued to bear down, and the confidence of some in the ability of the union to win began to erode. Pickets greeted the arrival of the scabs at the mine entrance with boos and shouting, and on at least one occasion “Maori war cries”. Each individual who scabbed was ‘followed-up’ by a group of picketing strikers and their wives shouting insults as they returned home. However, the Maoriland Worker was not mistaken in its assessment that very few Waihi miner-unionists could be induced to break the strike. Although a small number of unionists broke ranks, the increased number of scabs was due mainly to the recruitment of strike-breakers brought into the district from Auckland and other places. Their assignment was not to work but rather to provoke violent clashes with the unionists. And by the unionists’ own accounts, an increasing proportion of them were Māori.

The union leadership recognised the danger, but were completely at a loss to explain it.

(To be continued)

Pingback: The ‘white hope’ and the first alliance between Māori and the working class | A communist at large·