Last week I was invited to speak as part of a panel discussion on the question ‘What is capitalism and why must we oppose it?’ organised by the Platypus Affiliated Society at Auckland University, and attended by about forty students. The panelists gave a short introductory address, and then had an opportunity to respond to each other and questions from the floor. A wide-ranging discussion continued for almost three hours.

The other panelists were Robert Reid, a retired union leader at First Union, and Joe Hendren, a postgraduate student, former union organiser and member of the Socialist Society. Ricardo Menendez-March, Green Party Member of Parliament, was also scheduled to speak, but had to withdraw due to illness.

Publicity for the discussion stated:

The present is characterized not only by a political crisis of the global neoliberal order, but also by differing interpretations of the cause of this crisis: Capitalism. If we are to interpret capitalism, we must also know how to change it. We ask the panellists to consider the following questions:

What is capitalism?

Is capitalism contradictory?

If so, what is this contradiction and how does it relate to Left politics?

How has capitalism changed over time, and what have these changes meant politically for the Left?

Does class struggle take place today? If so, how, and what role should it play for the Left?

Is capitalism in crisis? If so, how? And how should the Left respond?

If a new era of global capitalism is emerging, how do we envision the future of capitalism and what are the implications of this for the Left?

The following is an edited transcript of my opening address, combined with my introduction and first responses to the other speakers, slightly expanded with a few points that I was unable to include due to time constraints. Platypus is intending to transcribe the entire discussion in a future edition of its monthly Platypus Review.

I joined the Socialist Action League in 1975, while I was a student at Victoria University. (The SAL later became Communist League). At the time I believed that revolutionary struggles were imminent worldwide. At first, my expectations were borne out: in 1979 deep-going working class revolutions toppled the monarchy and its death-squads in Iran, and brought a workers and farmers government to power in Nicaragua. I witnessed both of these firsthand.

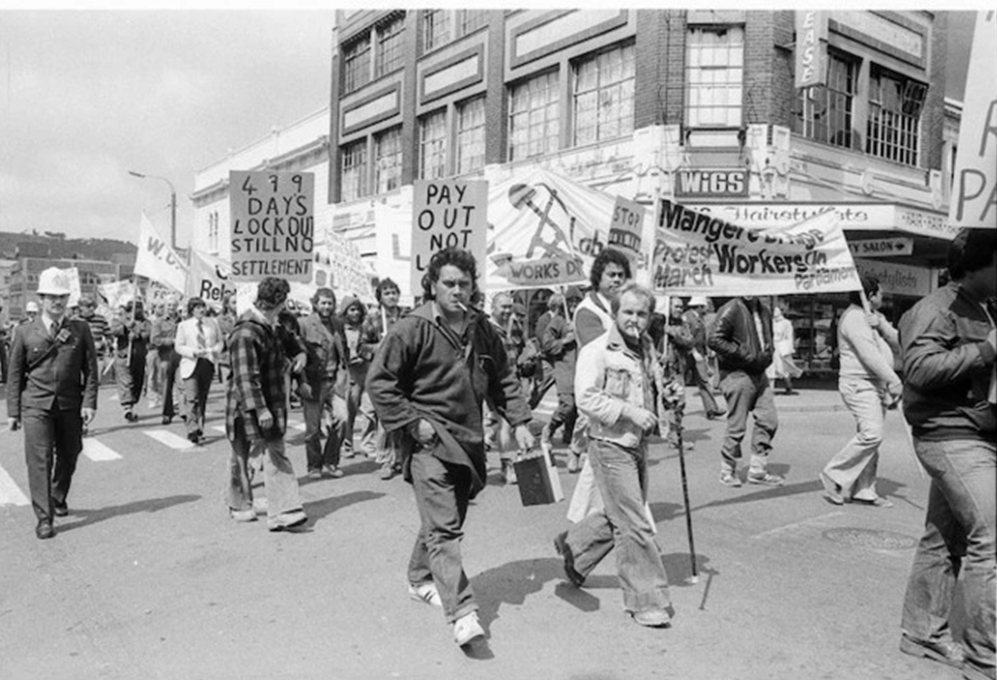

I took jobs in industry as part of the SAL’s drive to take its politics to the industrial working class – I worked in meat works, car assembly plants and other factories, and took part in strikes, the most important one being at Nissan in Wiri in 1986, the peak year for strikes in New Zealand.

But from end of 1980s history took a different turn. The revolution in Nicaragua succumbed to counterrevolution. Capitalism was restored in Russia and China. The union movement in New Zealand imploded, and the organised working class worldwide began a long period of defeats and retreat – the longest in the history of capitalism – and it’s not quite over yet. I withdrew from active political work in industry in 2000, and became high school teacher.

Ten years ago, I cut my last ties with the Communist League, and started my Worker at Large blog. I am back in industrial work now. Last year, I stood for Parliament in the Panmure-Otahuhu electorate, putting forward a working-class programme under the banner of Workers Now.

Capitalism is essentially a system where economic activity is dictated by profit, rather than human needs – the profit demands of the capitalist owners of the factories and mines, farms and forests, railways, shipping lines, and banks, prevail over human needs such as food, shelter, clothing, culture, and health care.

There is a widespread belief that the dictates of profit largely coincide with meeting human needs, through the mechanism of the market and its laws of supply and demand. There was an element of truth in that belief at least in the early phase of capitalist development, albeit at great cost to the dispossessed classes and peoples. Certainly, capitalism engendered a massive development of human productive forces, the greatest advance in the productivity of labour in human history.

But today, in capitalism’s senile phase, profit, and the laws of the capitalist market, are increasingly an obstacle to meeting human needs, especially social needs. How well does the market meet the need for fast efficient urban transport? Get on the Southern motorway in rush hour and you will see. How does the market meet the problem of climate change? By setting up the Emissions Trading Scheme, a new form of fictitious capital in which CO2 emitters pay indulgences for their sins and trade carbon credits, all of which has zero effect in reducing CO2 emissions.

The contradictions of capitalism are many: it gives rise to the sharpest class contradictions in human history, and therefore generates humanity’s most catastrophic wars.

I want to talk about one contradiction in particular: the way in which the competitive struggle of the capitalists to maximise their profits leads, in the longer term, to a general decline in the rate of profit. It is key to understanding why capitalism has a finite life span.

At the risk of over-simplifying a complex process I’ll briefly explain how it works1: competition drives each capitalist to replace workers with labour-saving machines. When they do, they gain a temporary profit advantage over their capitalist competitors. They produce the commodity cheaper, but sell it at the same price as their competitors. But the problem is, the value of a commodity is determined by the average quantity of labour embodied in it. Eventually, competition drives all the capitalists to invest in this labour-saving machinery. And when they do, the price of the commodity falls, because there is now less labour required to produce it. The capitalist’s profits might be the same as before, but relative to the capital they have invested, their rate of profit has fallen, because they have had to invest in the new machine. And it is the rate of profit, the return for each dollar invested, that matters most to them.

The effects of this falling rate of industrial profit became acute by the late 1980s, and so the capitalists have attempted to reverse it by various means.

They made significant cuts to real wages, they sped up the pace of work and lengthened working hours. They kicked out the legs from under the union movement – which was not difficult, since the unions had become utterly dependent on the state. They stepped up recruitment of immigrant workers under oppressive and exploitative conditions – whole industries like horticulture are now completely dependent on the superexploitation of migrants. Where I work currently, they replaced almost half of the workforce in the past year with new migrants brought in under the oppressive Accredited Employer Work Visa scheme, and a 12-hour working day is the norm.

But all of this was nowhere near enough to restore capitalist profitability. So they shut down entire industries and relocated to Asia, where wages were lower. The same closures took place across North America, UK and Europe. World industrial production is now concentrated to an extraordinary degree in Asia, especially China. Capitalism in US, UK, Japan and Europe has become largely parasitic, living off the financial and trade advantages inherited from the past.

So how does the falling rate of profit manifest in New Zealand today? It lies at the root of the most pressing social problems. These problems will not be solved short of the overthrow of the dictatorship of profit – and each of these by itself constitutes a sufficient reason to oppose capitalism.

- It is a major cause of capitalism’s failure to meet the basic human need for housing. When capitalist investment in production is unprofitable, capitalists seek more lucrative investment opportunities outside of production altogether. There is an element of gambling in all capitalist investment, and in the parasite economies they can get a better rate of profit on gambling without going through the messy process of production at all. These unproductive investments take the form of stock-market speculation, currency trading, gambling in fictitious capital of all kinds, from US Treasury bonds to debt packages, to soybean futures to Bitcoin, to scamming – all of which create no new value at all, but can be profitable. In New Zealand, the favourite form is speculation in residential real estate. The Reserve Bank lowered interest rates to encourage investment in production (the so-called ‘quantitative easing’ policy) and instead the investment flooded into the real estate market, pushing house prices (and thereby also rents) through the roof. There are 40,000 ghost houses in Auckland alone, left empty because the owners are simply using them as places to park their money and speculate on increased prices in future. A few years ago the Auckland mayor naively proposed a scheme whereby these empty houses could be matched with people desperate for a place to live. His proposal caused outrage – how dare he interfere with the capitalists’ right to do what they want with their investment!

2. It has generated unimaginable levels of debt – public, corporate and private debt – through which the wheels of commerce are kept turning. This makes the financial system extremely unstable. The overheated financial system is not something separate from the ‘real’ economy: when it collapses, it brings impoverishment and ruin to broad layers of people, both those burdened with debts and those who have none.

3. It is a spur to monopolisation. One of the few ways still open to the the biggest capitalists to raise their rate of profit is through monopoly price-gouging, using their monopoly position to buy at less than the market price, and sell at higher than market price. The supermarket monopolies do both, under-paying the fruit and vegetable growers who supply them, and over-charging their customers. Why did the Labour government correctly identify that the supermarket duopoly was responsible for monopoly price-gouging, promise to do something about it, and then, a few months later, announce that nothing would be done? Because the monopolies dictate to the government, not the other way round – whatever illusions parliamentarians may hold on that score.

4. Falling rates of profit are the underlying reason for the collapsing infrastructure, and growing threats to public safety and environment. For at least thirty years local governments and central governments, have been deferring necessary maintenance on water reticulation, roads, rails and ferries: hence the massive sinkholes that open up on city streets, the constant sewage spills into Auckland and Wellington harbours, the water leaks, the potholes in the roads. The exact same thing happens in the privatise sector: widespread cutting corners on safety and maintenance, risking lives. A year ago the Cook Strait ferry nearly ran aground, with 900 people aboard, because a rubber seal costing less than a thousand dollars hadn’t been replaced according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the ship lost power. It’s worth following the story about the Boeing plane with a door that flew off in mid-flight – a real scandal of corporate cost-cutting on maintenance, with the full connivance of the safety agencies of the capitalist government. The forestry slash which washes down the rivers and destroys roads and bridges whenever there is heavy rain on the East Coast, and which no one is held to account for, the inadequate rail maintenance which throws commuter rail systems into chaos in Auckland and Wellington on a regular basis.

You might think that the capitalists themselves need roads, reliable rail transport and ferries, clean water and so on in order to make profits. They do! They like lots of nice things. But if it comes to a choice between maintenance and safety versus this year’s profits, as it always does when the rate of profit continues to decline, profits will win. They want you to pay these costs! Now the Auckland Council has decided to collect household rubbish fortnightly instead of weekly, and to remove a bunch of rubbish bins from public parks – what could possibly go wrong?

5. The falling rate of profit even spawns its own ideology – whenever you hear talk of the ‘knowledge economy’, ‘post-industrial society’ ‘information age’ etc – you are hearing the universities attempting to rationalise the irrational, the attempt to make profits without production.

The ‘knowledge economy’ idea is a rationalisation of the system by which an Apple computer gets designed in Silicon Valley in California, actually gets made in China, then gets sold back in the US, and most of the profit from it goes to the US capitalists – profit without production! It rationalises the system by which the English language itself becomes a commodity for sale, packaged up in the form of ‘English language education,’ because the declining British and American empires established English as the primary language of international commerce. They suck profits out of it, just as they do from the dominance of the US dollar as the currency of world trade, long after the industrial supremacy on which these imperial privileges were based has disappeared.

Thinking and labour are inseparably connected, however – the human brain evolved in close connection with that less exalted organ, the hand. Capitalism severs this connection, dividing us into thinkers who don’t work, and workers who don’t think. (The worker who does think has, as Lenin puts it, already half ceased to be a slave.) The separation of thinking from working stunts and debases thinking, just as it makes labour oppressive. Ever more remote and detached from the labour process, the universities themselves, especially in the parasitic countries, become whirlpools of anti-scientific speculation and reactionary ideology, and the site of witch-hunts and cancel-campaigns. The despicable pile-on unleashed on the Listener Seven, academics who had the courage to raise unpopular ideas and opinions, is a fine example from right here at Auckland University.

And it goes without saying that these obfuscating ideological clouds serve to conceal from view the one social force which can put an end to the dictatorship of profit – the working class of the world. “The reasoning power and abilities of artificial intelligence make human labour obsolete,” it is argued. By “post-industrial” they really mean “without a working class.”

6. But the most important manifestation of the falling rate of profit is China. The historic shift of capitalist investment to low-wage China gave capitalism a 30-year extension of its senile phase. China was the rising tide that raised all boats, mitigating the effects of the Global Financial Crisis a decade ago. China’s extraordinary development meant that on a world scale capitalist production continued to expand throughout the last thirty years, during which the old imperialist powers have been mired in stagnation and decline. But now the long boom in China has ended – deepening financial instability, a debt mountain, and a gigantic real estate bubble have appeared there too. Like all imperialist powers, China will resort to military means to defend its profits. A confrontation between moribund US – which remains world’s greatest military power – and rising China is unthinkable in its catastrophic consequences, but also inevitable, if the world working class fails to prevent it. This war is not exactly imminent – Australian and New Zealand capitalists, for example, are not going to rush into a war against their biggest trading partner, on whose economy their prosperity rests! – but US-China conflict is nonetheless the axis of world politics from here on. Only a mobilisation of the working class to overthrow the dictatorship of profit can avert it.

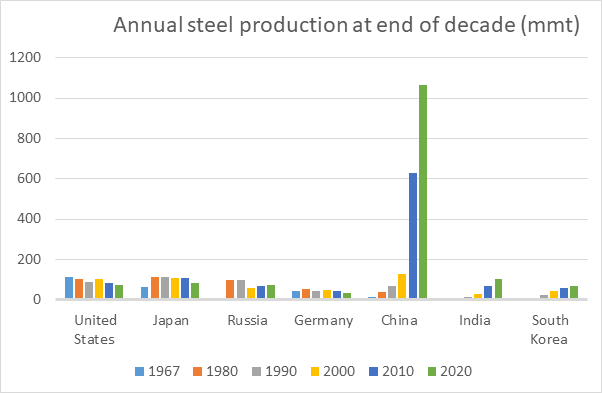

Robert said that our thinking lags behind the current reality. This is very true, and nowhere more so than in catching up with the historic shift of the centre of gravity of world capitalism from North America to China. China is by far the largest economy in the world in terms of value created. You will often read that China is second-biggest, measured in Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But GDP is not an accurate measure of value created, because it includes in it all manner of activities that produce no value – every bitcoin purchase, every real estate sale – and is thus grossly distorted in favour of the parasitic economies. A far better indication of the relative size of industrial economies is steel production. (See the graph below)

Is there a class struggle? Yes there is, but at this point, a very muted one. We are on the point of coming out of the longest unbroken period of working class quiescence and retreat in history of capitalism – more than thirty years and counting. China is the key to understanding this too: working class power and self-confidence had been concentrated in the advanced economies, the industrial powerhouses of North America, Japan, the UK (albeit already declining) and Europe. The process of de-industrialisation of these regions through the historic shift of capital to China robbed the working class of some of its power and weight in the old countries, and workers correctly sensed this shift.

On a world scale, the working class is numerically and economically stronger than ever, but now it is centred in China and Asia. (In China, workers had been dealt some savage blows by the counter-revolution – especially the perversely named “Cultural Revolution,” and the repression of Tian an-Men in 1989 which left them atomised and disoriented. The extraordinarily favourable circumstances of China’s capitalist development, above all the massive flow of capital into the country from outside, meant that unlike every other advanced capitalism, China was able to raise the living standards of the toilers simultaneously with this expansion.) The consciousness of the world working class has yet to catch up with these momentous changes.

It doesn’t mean workers are powerless in a country like New Zealand – they remain the only class that can lead the way out of the capitalist morass – but it does mean a complete break with the past: all the old organisations and institutions fall apart, new ones have to be built almost from scratch. It is not the first time such a complete rupture has taken place – something similar occurred with the outbreak of war in Europe in 1914. Yet only three years later the Russian revolution took place.

Both the other panellists have mentioned Marx’s famous dictum: “The philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” It is very true, but it’s not easy to know where to begin. The most important thing – and in the present circumstances, not the most obvious – is to align yourself with the social forces that are capable of changing the world. The working class remains, as Marx described, the only truly revolutionary class, the class with nothing to lose. You don’t have to be a worker to be part of changing the world, but you do have to find a way to connect with the working class, and to join in unleashing its economic and political power. You do have to take, as your guide to action, whatever advances the interests of the working class – its unity across the divisions of race, nationality, sex, religion, immigration status, skills, employment status and so on which the capitalist class foists on us, its self-confidence, its independence from capitalist politics.

This is what we were attempting to do with Workers Now – to think through all of the current political issues from the point of how do we strengthen the unity, self-confidence and political independence of the class, and present these ideas in our literature (I have some copies if you would like to have a look) as the starting point for our political discussions. An election campaign is quite a good way to do this, and to reach a broad audience. One thing we noticed is that outside of the factory itself, there is nowhere that workers are more class-segregated, and at the same time, racially and ethnically integrated, than in the housing suburbs. Such campaigns are a good entry point to class politics. We will be continuing these campaigns in future, and I invite anyone here to join us.

Footnote

- A more adequate explanation be found in Volume 3 of Marx’s Capital, in Part Three, Chapters 13 to 15. For a succinct discussion of the question as it occurs today, see The falling rate of profit and other explanations of capitalist crisis, by Terry Coggan.

I agree with your thesis. I have been a Union member all my life and believe that the Union movement is responsible for all the social and material improvements we experience today. The fact that Governments all round the world have tried and are still trying, to crush Union movements says it all. As the inequities in society grow ever larger it is obvious Capitalism is not the answer. Or at least not the answer for the vast majority of people! The struggle continues.

Thanks for sharing. Our kiwi background is similar except I am a bit older and remember being told not to run when unloading railway trucks at the Waltham C Shed. I later became a union delegate and was a PSA member when Douglas and co gifted the Housing Corp to Fay Richwhite. Even earlier I was a spectator in parliament when Muldoon screamed at McGuigan, in the Chair during one of the readings of Labour’s Superannuation Bill, that it was communism through the back door and would pave the way for Labour to buy controlling interests in New Zealand companies like NZ Forest Products Ltd. If that Kirk scheme had continued NZ would now be a lending nation not a borrower. Anyway my two bits is that evolution and that looming conflict you describe, will within the next decade force human kind, to emulate the great population break out of the 1400’s (Americas and Aotearoa) and settle Mars as a first step

I take a more pessimistic view and dare to opine that global human expansion is where Europe was in 1492 when the invasion of the Americas began, as did the settlement of Aotearoa. Next stop Mars