Second of two parts. The first part, “Half-caste Maori” strikebreakers at Waihi and Huntly, is here.

After the mine re-opened on October 2, the number of police, strikebreakers and thugs brought in to Waihi grew rapidly, and the pushing and shoving on the streets between them and the union-loyal miners became more violent.

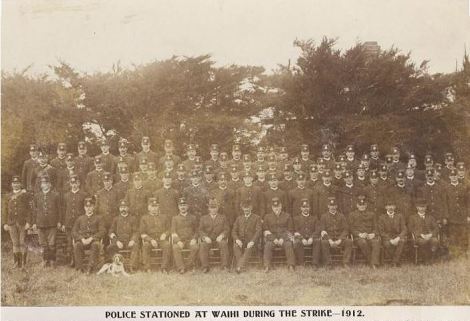

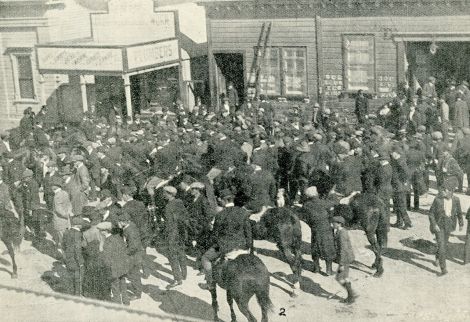

By November there were 90 police sent to Waihi despite the fact that there were few disturbances of public order before they arrived. Photo: Ohinemuri Regional History Journal

“One of the most prominent workers who signed on at the Waihi Company’s mine on the first day of the resumption of work is a six-footer Maori, who is well known as the ‘white hope’,” reported the Poverty Bay Herald on 26 October. “He is a most combative individual, fears no man, and has challenged all and sundry to ‘have a go.’ His arrival at Waikino was marked by rather a dramatic incident. Instead of getting out of the train at the railway station proper he disembarked in the Waihi Company’s yard. The strike pickets pointed out to him that that spot was not a station. The visitor replied that he had arrived at his destination and was going to work. That settled it, and the ‘fat was in the fire’ immediately.

“When getting his traps together a pair of blood-stained boxing gloves tumbled out, which acted in a somewhat soothing manner upon the pickets, who by this time were frankly reeling off their several and varied opinions anent the Maorilander’s advent. When he arrived by the company’s train on the morning of the 2nd inst., he took up a position on one of the tipheads in full view of the crowd below, and executed a Maori haka in fine style. Later on he lodged at the Central Hotel instead of proceeding every day to Waikino.” Further details about this individual were added by the Auckland Star: “The police have had many anxious moments in watching their dusky charge. He hails from Paeroa way, and is said to be an ex-college boy.”

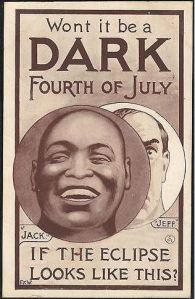

The fact that this man was called the “white hope” might seem incongruous at first glance, since he was Māori, not ‘white.’ In the historical context, it is more easily understood.

The first ‘ Great White Hope’ was James Jeffries, and his expected victory over Jack Johnson was scheduled for 4th of July.

Jack Johnson, a Black American boxer, had won the title of World Heavyweight Champion in 1908, in a fight in Sydney, Australia, and held the title for seven years. Johnson had to overcome the huge racist obstacles of the Jim Crow era; his victory upturned racist conventions about racial segregation and the inferiority of Black people, and inspired Black people across the globe. Johnson married a white woman and opened an unsegregated night club. For the seven years of his reign as champion, white supremacists longed in vain for a ‘Great White Hope,’ a white boxer who could defeat Johnson and ‘put the African in his rightful place.’

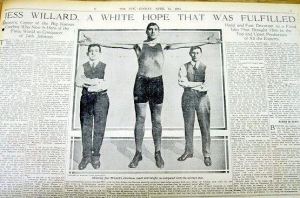

The challenger Jess Willard was also described as the ‘white hope’. Willard defeated Johnson in 1915.

It appears that a similar longing for a fighter who would put the rebellious Waihi workers ‘in their rightful place’ motivated the enthusiastic description of this strikebreaker as the ‘white hope’. (Jack Johnson was arrested on frame-up charges – at about the time the Waihi strike was ending – and was eventually jailed.)

In the scuffles and street fights that broke out over the following weeks between the union miners and the scabs, other strikebreakers distinguished themselves, including one named “Harvey the Pug” (for ‘pugilist’), a Maori named “the Snake Charmer,” and another described in The Colonist as “’Peter the Painter,’ a Maori of considerable bulk, but no science … who adopted a most conspicuous swagger.” (The name “Peter the Painter” is another somewhat inappropriate reference to events of the time. In January of 1912 three Russian anarchists accused of the murder of a police officer died in a spectacular police siege of the building where they were staying in the Jewish quarter of London.

Winston Churchill directing the assault on the anarchists in January 1912. Churchill is the left one of the two figures wearing top hats.

After a shootout with 700 police, personally directed by Home Minister Winston Churchill, a fire destroyed the building and its occupants. One of the wanted anarchists was known as “Peter the Painter.” He apparently escaped the fire, and his whereabouts became a subject of much speculation.)

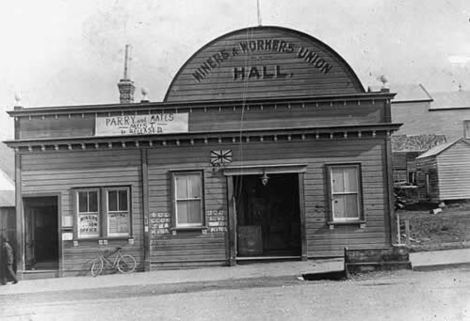

Waihi Miners Union Hall during strike. Banner top left says “Parry (union president) and mates must be released.” A scab has painted the Union Jack above the door and “God Save the King” beside it. The unionists have altered this in turn to “God Save J B King,” the name of a visiting IWW agitator. Photo: Alexander Turnbull Library Waihi Arts Centre and Museum Collection, Reference: F-W 021950-1/2

The Waihi strike ended abruptly in early November, not by the company successfully resuming mining operations with the labour of strikebreakers, but through a violent assault on the union of the miners by the scabs and thugs. On 12 November a crowd of armed scabs, with the active support of the police, forced their way into the Union hall, routing a small number of unionist defenders, and took possession of it. In the melee, one cop took a gunshot wound and a striker defending the hall, an Engine Driver named Frederick Evans, was beaten to death by the cops and thugs. The triumphant scabs then took possession of the streets as well, and again with the full cooperation of the police, drove the unionists out of town by means of guns, batons, and kerosene and matches.

Crowd of police and scabs outside union hall (the building on right) shortly after it was stormed, 12 November 1912. The boarded-up windows were smashed in an earlier attack by the scabs. Photo from Auckland Weekly News 21 Nov 1912. Archives Reference: archway.archives.govt.nz/ViewFullItem.do?code=21948546

By that time, according to the union, Māori made up a majority of those entering the mine each day. Some weeks later Herbert Kennedy, the union president appointed after the first president was jailed, testified in court that “To the best of his belief the statement in connection with his reference that two-thirds of the workers in the mines were half-caste Maoris, and that the pahs in the Thames had been circularised to obtain them, was correct. He counted 158 men going to work on a certain day, and he estimated that over 100 of them were half-castes … He had seen a circular from one of the pahs offering men work. He did not know the author of the circular. The circular in question was printed in the Maori tongue. He did not know Maori, but it was read out to him by a Maori.”

Strikers gather outside Waihi law courts 1912. Photo: Waihi Arts Centre and Museum

The Māori strikebreakers played a prominent role in the court cases relating to the assaults and violence of the last days of the strike. Harry Holland reported in the Maoriland Worker that “The Worker representative counted 25 Maoris, mostly half-breeds, in the vicinity of the court, at a time when about a hundred persons in all were present … When the court opened on Wednesday the big Maori who carries the nickname of the “Snake Charmer” occupied a chair inside the railing, and near him sat Mr. Barry, the mine superintendent. The big Maori held a big pipe in his hand and wore a big scab badge in the lapel of his coat. On the previous day, when the union vice-president, McLennan, sat inside the rail, he was ordered out by the police, who even refused to let him stand outside the rail near the union’s solicitor.”

These developments were quite shocking to the unionists, and their first attempts to account for the phenomenon of Māori strikebreaking were lamentable. Even Harry Holland, who had a proud record of fighting racism – he had strenuously opposed the White Australia policy, and denounced the racist and chauvinistic policy of the union movement towards the Kanaka labourers in the Queensland sugar plantations – nonetheless fell back on the reactionary language of racial purity when attempting to explain it.

Holland’s book about the strike, co-authored with Maoriland Worker editor Bob Ross and Frank O’Flynn, The Tragic Story of the Waihi Strike, contains the following passage: “The gold-owners circularised the Maori pahs, and held out inducements to the Maoris to scab, and they enmeshed a multiplicity of half-castes and quadroons and octoroons but scarcely any full-bloods. “The full-blood Maori never scab,” said a venerable chief. “It is only when he get the white blood in him he scab.” And so, with toughs and thugs and gun-men from the cities, Maori half-breeds and tribal outcasts from the pahs, and those physical and moral degenerates among the whites who figure as professional scabs, the companies made up that fearsome aggregation that the capitalist press, the hireling lawyers, law-makers, and law administrators found so much dull and humorless satisfaction in deferring to as “the workers.”‘

In the language of racial purity, quadroons and octoroons are the terms for quarter-blood and eighth-blood respectively. Reading this passage today, it is hard to believe that the unnamed ‘venerable chief,’ with his imperfect English, was anything but an expression of Holland’s own historically-conditioned ignorance. After another century of intermarriage between Māori and pākehā, the listing of fractions of racial blood as an explanation of anything can only appear to modern readers as both ridiculous and offensive.

But it was ignorance, rather than prejudice. The weird and essentially racist contortions the Federation side were forced to engage in to explain Māori strikebreaking, despite the fact that they “rejoiced in the non-existence of the colour line in this country,” can be traced to their blindness to the national oppression faced by Māori.

It was true that, due to their military dominance at the time of the founding of the New Zealand colony and for many years afterwards, Māori enjoyed formal equality under the law. It was true that this was a far more favourable situation than that faced by Black Americans under Jim Crow law, or Australian Aborigines under the laws of ‘terra nullius,’ or Africans in the Cape Colony. It was true that this placed the entire working class in New Zealand in a more favourable position than workers in those countries. Those facts were certainly worth rejoicing.

But it was not true that Māori enjoyed equality or freedom from national oppression. The strikebreaking by Māori at Waihi had brought the newly-developing labour movement face to face with the fact of the dispossession and discrimination against Māori in New Zealand society. The nature of the national oppression of Māori was something that the Red Fed leaders had yet to learn. They were, however, capable of learning and, in the course of the struggle, they did learn.

Meanwhile, the problem was not about to disappear.

When the first batch of arrested unionists from Waihi were transported to jail in Auckland, some large demonstrations in solidarity with them were held, including a march by 3,000 workers from the Auckland waterfront, who met the boat carrying the prisoners at the wharf and marched alongside them to the jail. On the same day, at the coal-mining centre of Huntly in the Waikato region, the miners stopped work for a day in protest.

The Huntly coal bosses then raised the stakes, locking out the miners there, and sacking the union executive in the mine. With the defeat of the strike at Waihi, they looked to press their advantage at Huntly, and attempted to organise a scab union in the mines. As at Waihi, they sought to recruit local Māori into this effort.

This was a little more difficult for the bosses than at Waihi, mainly because among the members of the Federationist union there were some Māori miners. A report from Huntly in the Maoriland Worker on 1 November reads: “Rumor through from Maoris that 30 had joined new union, they having been told 25 pakeha had already joined. October 21. 5.30 a.m. Six members visited Maori pah to ascertain truth of rumor and persuade them to refrain from work. At 6.30 a constable arrived. A slight scene ensued owing to the attitude adopted by the constable, who is evidently new to this kind of work. Five Maoris essayed to go to work. The constable rode across the river with them, the pah being on the opposite side of the river from the mines. A big crowd met the Maoris on the town side. There was no demonstration; simply a silent stare … October 24. Two Maoris turned out to work. The Maori members of the Union brought inside pressure to bear on their fellows to cease work; the two at work are not Huntly natives, we are led to believe.”

Once again, the Maoriland Worker raised the alarm about the danger this situation presented to Māori as well as unionists. “To what depths will the hirelings of Capitalism sink to gain their foul, filthy, dastardly, deadly ends! Social opinions, political opinions, national opinions and religious opinions are used with the chief end of dividing the workers among themselves that they may defeat themselves. But this subtle slimy, snake-like, treacherous act at Huntly to create a color line in New Zealand by estranging the pakeha and Maori ranks as the most despicable of all treacherous acts aimed at a noble race by unscrupulous pakehas. Create a color line here and confiscation of native reserves follows as night follows day, while the extinction of another noble race will soon follow.”

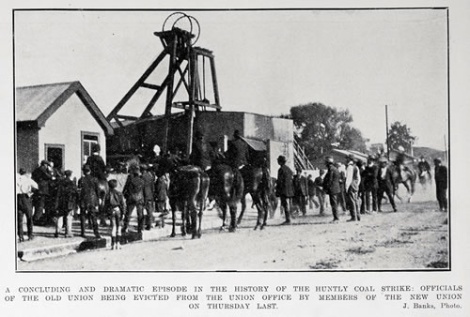

The scab union was eventually formed at Huntly, and registered under the Arbitration Act with 93 members in early November. Under the terms of the Arbitration Act, this then became the legally recognised union for all the miners, despite the fact that a far larger number had chosen to de-register and join the Federation. The Huntly coal miners were now in the same position as the Auckland labourers and the Waihi miners.

But the Huntly coalfield happened to be located in the Waikato, at the heart of the Kīngitanga (King Movement), the leadership centre from where some of the most determined resistance to colonial encroachment on Māori land had been led a half-century previously. The traditions and spirit of the Kīngitanga were still very much alive at this time. In the midst of the union struggle at Huntly coal mines, the third Māori king, Mahuta Tāwhiao, died on 9 November, and his son Te Rata Mahuta became the new king two weeks later.

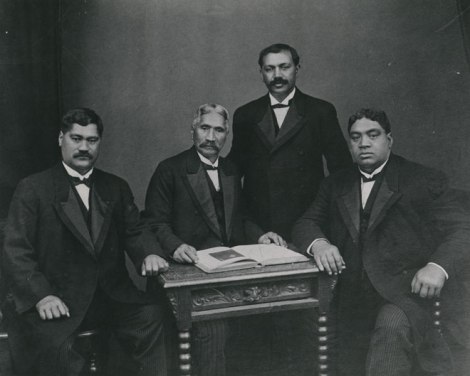

Te Rata Mahuta, left, with Kingitanga officials on visit to King George of England 1914. Photo: Auckland War Memorial Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira Reference: GN672-1n18

Te Rata must have had a sense of what was happening in the nearby coal mines. An article in the Maoriland Worker dated 6 December reads, “Few are the kings of these modern days who rely on loyalty and love as the foundation and support of their thrones. In this respect Te Rata the Maori King, is king of them all. It is interesting to note that the white wage-slaves and the native Kaimahi [workers – JR] resident here and working in the mines have a staunch friend in Te Rata. During the recent cessation of coal-getting in Huntly, Walsh [organiser of the scab union – JR] endeavoured to organise scabs among the Maoris. He succeeded in getting six on promise of big pay. The pickets reasoned with them and one returned. Te Rata saw the president and secretary of the union and promised to intercede; he did: result, no Maori scabs.”

I don’t know the names of the union president and secretary who took the initiative of speaking to King Te Rata. Most probably they were among the union executive sacked for demonstrating their solidarity with the Waihi workers, and subsequently forced by the blacklisting to leave Huntly. The names of the Māori rank and file union coalminers, who also played such a key part, are also unknown. They deserve greater recognition, as does Te Rata himself, for this act. It was perhaps the first occasion that a central leader of the Māori people had openly aligned himself with the fighting union movement in New Zealand.

Union miners being evicted from the union hall at Huntly by members of the Arbitrationist scab union and police in January 1914. This was the final defeat of the fighting union in the mine. Months later, an explosion killed 43 miners. Photo: Auckland City Libraries Ref: AWNS-19140122-54-2

After a couple of years of back and forth victories and setbacks, the fighting union at the Huntly coal mines was defeated despite their efforts (with tragic results a short time later.) But the alliance between the Māori nation and the working class that was formed in the heat of that struggle proved more durable. It developed, strengthened and spread over the next twenty years. In part this was based on a common opposition to the World War and conscription. Te Rata opposed military conscription, as did Holland, Fraser, Webb and all the leading Red Feds. Te Rata’s younger brothers were among the Waikato Māori targeted by a campaign of persecution on account of their opposition to conscription; one of them was imprisoned at Narrow Neck naval base along with a number of other objectors to conscription. Beyond the Waikato, the alliance later deepened in the Rātana movement of the 1920s and thirties. Harry Holland played a part in cementing this alliance, which lasted in one form or another for seventy years.

As far as I am aware, in more than a hundred years since that time there has not been another instance of strikebreaking in which Māori played a major role.

Hi James

Fascinating article. I hadn’t known about the involvement of the Kingitanga with the Huntly miners.

I’ve always felt that two key weaknesses of the early Socialist Party and the Red Feds in New Zealand were their failure to see the need and the possibility for the working class to forge alliances with Maori fighting for their national rights, or with working farmers. Of course it’s easy to say that in hindsight – at the time they didn’t have the example before them of the Bolshevik Revolution on these two vital questions.

The tragic irony is that by the time the Labour Party in the 1920s did reach out to Maori, through its alliance with Ratana, and to working farmers, with policies of guaranteed prices etc., it had become a thoroughly reformist parliamentary formation.

As I’m sure you know, there was one current at the time that, despite all its political weaknesses, did show an awareness of the importance of the national question, and that was the IWW. In 1913, their short-lived paper, The Industrial Unionist, did carry articles in the Maori language appealing to Maori not to act as strike-breakers, and pointing out that the boss class that was attacking workers and their unions was the same class that had confiscated their land.

Thanks for your comment Terry.

On the ‘two key weaknesses’ you identify: I think they are really two aspects of the same weakness, namely, an over-simplified, essentially syndicalist conception of socialist revolution. They expected that capitalist society would rapidly polarise into two warring classes, the capitalists and the proletariat, before the struggle for power – this idea appears often in their literature. That polarisation is certainly a tendency of the evolution of capitalism, but is not necessarily complete by the time the seizure of power is posed. If the syndicalist conception (which the IWW shared with the Red Feds) were true, there would be little need to pay much attention to the disappearing middle layers like small farmers, national oppression was, or soon would be, largely irrelevant, and there would be little need for political struggle and alliances. The conception of the proletariat leading all the oppressed and exploited layers of capitalist society in the struggle for political power, including the non-proletarian classes and nationalities, was, as you say, a Bolshevik one. In Russia, the proletariat was a small minority of society, and the Russian empire was a vast ‘prison-house of nations,’ so communists there were obviously confronted with the need for those alliances in a very stark way. I doubt that those forces in New Zealand who identified with the IWW were qualitatively different from the Red Fed leaders in this respect. Their 1913 appeals to Māori workers in te reo Māori are certainly a vast improvement on Harry Holland’s paragraph quoted in my post, but this was a period of intense ferment, and I think a further year of the lessons of Huntly and experience in the broader class struggle accounts for the difference. The 1913 mobilisation of farmers against the working class certainly caught both currents equally by surprise.