It is easy to underestimate the current ideological and political drive against women, and the degree to which it threatens the gains made in the struggle for women’s equality from the 1970s onward.

Rally outside New Zealand parliament for abortion rights, 1977. There was a mass movement for women’s rights in the 1970s and 1980s.

This may be partly because discussion of the ideas at issue has until recently been largely confined to feminist discussion forums and academic and health advocacy circles, much of it online, and only now is the discussion spilling out into a broader arena and starting to have an impact on public policy.

But a more important reason is that supporters of women’s rights have been blindsided. Having grown accustomed to expecting attacks on women to come from the political right wing,1 some have been caught off guard by the fact that the latest wave of misogynist ideology has come from the left-liberal wing of bourgeois politics. The new drive against women takes the gains of the movements for women’s rights and gay rights as its point of departure, and masquerades as an extension of these gains. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The question of prostitution is a case in point. Until 2003 prostitution was illegal in New Zealand. The crime on the law books was ‘soliciting’ – in other words, the client was the victim and the prostitute was considered the criminal. On top of the sexist violence that was frequently their lot, prostitutes faced the constant threat of police harassment and criminal charges. (There was no legal sanction against the ‘client’.) A pall of stigma and shame hung over the prostitutes, aggravating the already high risks to sexual health: for a woman to be found in possession of a condom could be used as evidence that she was ‘soliciting.’

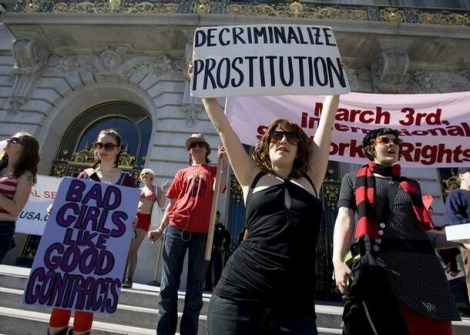

In the context of a rising mass movement for women’s rights in the 1970s and 1980s, prostitutes in New Zealand began organizing to demand elementary civil rights and protections, and sexual health services. They formed the Prostitutes Collective, which campaigned to bring prostitution out from the shadows and remove the stigma of shame that surrounded the practice. Thanks to this effort, and spurred by fears of the spread of AIDS, eventually prostitution was decriminalised in 2003.

It was undoubtedly a step forward when that legal threat hanging over the prostitutes was removed. Decriminalisation enabled prostitutes to demand legal protection against rape and other forms of sexual assault by their clients on the same basis as any other woman, and made it easier to take public health measures. Legalisation of prostitution followed on the heels of the law changes criminalising rape within marriage, and there were some well-publicised and successfully prosecuted criminal cases where prostitutes accused their clients of rape.

Although in broad outline these trends were international, full decriminalisation of prostitution remains fairly rare in the world – such that this has become known internationally as the New Zealand Model of prostitution legislation.

But decriminalisation of prostitution was very much a double-edged sword. Full decriminalisation also removed penalties for pimping and brothel-keeping, and thus removed barriers to the expansion of the sex trade; its most far-reaching effect was to normalise the practice.

Normalisation of prostitution: Advertorial article in NZ Herald about Hamilton brothel seeking prostitutes during Fieldays Agricultural Show week

Consequently, the sex trade aggressively expanded out of the back alleys onto the main street and into the suburbs – so fast, in fact, that local authorities had to rush through new bylaws against opening brothels right next door to schools. The sex trade grew in parallel with the explosive growth in the circulation of pornography – and in mutual dependence with it. Both of these social ills were symptoms of sexual alienation and of a breakdown in relationships between men and women in capitalist society. Both of them accelerated and deepened that malaise.

At the same time, a literature grew up which sought to re-cast prostitution as the ‘sex industry,’ and prostitutes as ‘sex workers,’ implying if not explicitly stating that they are like any other worker in a service industry. Mainstream media articles prettifying the sex trade (and helping to recruit for it) are increasingly commonplace.

Take for example this recent article in the Victoria University student newspaper Salient: “Since engaging in sex work I have begun to reclaim my sexuality and ownership of my body. For the first time in my life I fully enjoy sex without feeling self-conscious or guilty. I feel beautiful and strong, and no longer allow myself to be pressured into sex.”

Feminist writer Renee Gerlich traces the source of articles like this to the ‘misleading tripe spun by pimps.’ She has written a critique of such literature here.

The New Zealand Prostitutes Collective has been at the forefront of the effort to normalise and promote the prostitution ‘industry,’ under the slogan ‘sex work is work’. Its website takes for granted an identity of interests between prostitutes and their exploiters; for instance it states, on its page ‘For brothel operators’: “If you are considering starting a brothel, or you work with sex workers in your job, NZPC can provide valuable information. We support sex workers to have options in how they work, and brothels to provide safe and sustainable working environments, free from exploitation, coercion, and fines. We can provide you with resources that help your business to stay within the law and provide a safe and sound venue to seek employment.” The Prostitutes Collective describes itself as “a crucial point of liaison between government and non-government civil society, and the sex industry”. It operates Ministry of Health contracts for sexual health services, and functions almost as a government agency.

But ‘sex work’ is not just ‘work like any other,’ even if there are women (and men) who choose to make their living that way, and who need the protection of the law. The capitalist mode of production turns labour into a commodity to be bought and sold: it requires the wage-labourer to surrender a portion of their labour to the employer, unpaid. Prostitution requires the prostitute to surrender her entire being, her physical and conscious self, including her dignity, to be bought and sold. In this case it is not labour that is commodified, it is the human being herself. The comparison with wage labour is false to the core.

Recognising prostitution as ‘work like any other,’ would mean, for example, that an unemployed woman worker judged to be a suitable applicant for this line of ‘work’ could be required to take up such a ‘job offer’ or forfeit her unemployment benefit.

Prostitution after decriminalisation remains prostitution: a deeply oppressive institution which degrades women to the status of a commodity, a malignant cancerous excrescence on the body of capitalist society. The size of the excrescence is an indication of how far the sickness of capitalism has advanced.

The re-invention of prostitution as some kind of road to sexual liberation for women has not gone unchallenged, of course. Many feminists have decried the normalisation of prostitution and pornography in the strongest terms, and have subjected the associated false ideas to detailed critique. (Feminist Current is one example among many.) However, those who challenge it today can find themselves accused of denigrating sex workers and ignoring the voice of those ‘working in the industry,’ and subjected to intense abuse, no-platforming and censorship of their opinions.

For example, when Renee Gerlich challenged the Salient article on their Facebook page, and posted links to other articles supporting a more critical view of prostitution, her comments were deleted by the magazine’s editors ‘at the request of the author [of the article]’ while a stream of abusive comments against Gerlich was left in the thread. After coming under further criticism for this cowardly act of censorship, the editors pulled the link from their Facebook page and shut down the discussion completely. The new liberal misogynist orthodoxy does not tolerate dissenting opinions.

Notes

- Attacks from this quarter have not abated. On 1 September a new law comes into effect in Texas further restricting women’s access to abortion.

To be continued. Next post: “Trans women are women” – misogynist ideology and public policy in the guise of transgender rights

A difficult topic. I note a fleeting nod to male prostitution which like female prostitution has existed since time immemorial. The oldest profession no less. It seems to me your thesis has a primary focus on women and I wonder if you had focussed soley on male prostitution the same conclusions would have applied . I def agree that exploitation exists but I think/hope decriminalization may have reduced that by applying the protection of general labour law. In NZ at least.

Thanks for your comment, Winston.

On ‘the oldest profession’: I think this often-used phrase is misleading in several ways. For one thing, prostitution is not a ‘profession’ for much the same reasons that it is not ‘work’. And while it is certainly an old institution, pre-dating capitalist society by thousands of years, it does not quite go back to ‘time immemorial’. It did not exist during the first 99% of human history, the period of primitive communism, in which women held high social status. It originates with the rise of class society (one of the first forms of which was slavery) which was also the period when women were transformed into a commodity in other ways as well. The ‘world’s last remaining form of slavery’ might be a more accurate phrase.

On male prostitution: I read the figure somewhere that about 85% of prostitutes in New Zealand are female, the rest are male. I don’t know where that figure comes from, in which category it places transgender prostitutes, or how accurate it is, but it seems reasonable to me as a rough estimate. Keep in mind also that all or almost all of the male prostitutes are servicing male clients. Is there a form of prostitution where women pay for sex? I’m not especially knowledgeable about these things, but I am not aware of such a thing. If it exists at all, it is entirely marginal to the institution. With these facts in mind, the only sensible way to see prostitution is as an institution whose primary function is the enslavement of women, which also extends to enslave some men.

I support extending the protection of the law to prostitutes, including workplace health and safety laws, and decriminalisation certainly made that possible. I wouldn’t call it ‘labour laws’ though. And doing so doesn’t ‘solve the problem’ of prostitution.

Def agree with some of the points you make. I do wonder though if you are taking a moral position as opposed to making a neutral observation about what you perceive as a form of slavery. Where I disagree is your conclusion that the trade cannot be profession. Where I do agree is when people are coerced into it. I liken that to the crime of rape.

I am a happy healthy professional escort and decriminalization is the only way to move things forward for women’s rights and specifically sex workers rights. I generally don’t trust right wing men masquerading as champions for women’s rights.

Thank you so much for writing this article. I especially loved this: “Prostitution after decriminalisation remains prostitution: a deeply oppressive institution which degrades women to the status of a commodity, a malignant cancerous excrescence on the body of capitalist society. The size of the excrescence is an indication of how far the sickness of capitalism has advanced.”

I do think there is some discussion to be had on the detail of the law, and maybe people advocating for decriminalisation sometimes make good points, but at the moment when I see people (on the left) criticise the abolitionist model I have noticed a few things in common in how they present their arguments:

1. They ignore what actually takes place in prostitution.

This involves ignoring the power dynamic between the woman and client (normally a man, where the power is more in the mans hands than the woman’s), the woman and her pimp and/or landlord, and ignoring the actual acts the women are expected to perform over and over again (on men they would not chose to have sex with otherwise). It is very noticeable that the abolitionists give examples about what happens in reality, and the people arguing against the Nordic model do not. It is hard not to side with the Nordic Model once one sees what actually happens on the ground. To me it sounds more like slavery than waged work.

2. The often repeat arguments put forward by the pimp lobby, sometimes seeming to be oblivious to what they are doing, though sometimes they know they are doing this but do not acknowledge it.

3. And they make utopian claims about prostituted women organising in Unions, even though the evidence is against this happening, and the “unions” are often controlled by pimps, or atypical sex-trade workers.

4. They ignore that full decriminalisation seems to lead to an increase in women coerced into the sex trade, due to the “need” for the supply to meet the demand. This is one of my main worries about decriminalisation.

I am in an organisation, meant to be Marxist, who are currently really pushing arguments that to me sound like they are regurgitating pimp propaganda, and also coming from a very liberal/neoliberal point of view. This is one of the articles http://www.rebelnews.ie/2018/09/13/irish-state-failing-sex-workers/

They do not acknowledge the massive propaganda machine that is behind the decriminalisation movement, either to themselves I think, or to others.

They did great work on the abortion referendum, but the legislation to legalise some abortion services is not even in yet and it feels like they are already helping to put women back on their box.

I do not know whether I should stay in the group or leave now. I was going to try to raise some issues at the AGM next year, but it seems hopeless now. They are also terrible on the trans issue, completely throwing women under a bus there, and I am a “terf” and “transphobe” for raising concerns. But that is a whole other story.

I just can’t believe this group, which was staunchly materialist, has gone all post-modern-neoliberal on me. My two pet hates. I guess the pressures are there and can happen to anyone.

Thanks very much for your comment. I had been wondering whether the big public debate around the abortion referendum meant that the dynamics of this discussion might play out a little differently in Ireland – unfortunately, that doesn’t seem to be the case. Your observations seem all too familiar to me, at the opposite point of the globe.

Thank you Robb. As far as I can make out, Liberal Feminism, with the emphasis on individual choice and personal autonomy, is the main type of Feminism here, and was very prominent during the referendum campaign, though socialists were key to starting and setting up the campaigns initially.

In some ways this emphasis on autonomy was/is an improvement over the previously stifling attitude of having to put up with all sorts of things on the grounds that it was God’s will, or just the way it was, which encouraged a passive attitude politically. But I think the Liberal way of thinking leaves a lot to be desired in terms of an analysis of things like prostitution and transactivism, where the context of the “choice”, and impact on society, needs to be looked at. In any case, I think most women involved in prostitution would not claim to be making a free choice, and would get out of it given other options. The abortion issue is a bit different, in that it was the woman taking the pregnancy risk herself, with her own body, so should have a choice whether to do this or not.

Unfortunately, I think Liberalism has influenced the Marxist left here, but I don’t think they can see it. This is my impression, though I may be wrong. Some of the push regarding legalising prostitution (and the push for “trans rights” as it is put) seems to be coming from younger people, who I suspect are heavily influenced by neoliberal ideology, individualism, and living in a highly consumerist society. I do think the leadership of socialist groups, who have more experience and probably a better grounding in Marxist ideology, have a lot to answer for for not showing better leadership on these issues.

I am going to try to read up a bit more on socialist and Marxist theory myself, to get a better grounding in the ideas. It might help me to make better arguments, and I like reading different perspectives anyway. I have really enjoyed reading your articles. Thanks for putting so much work into them. Lots to think about in them.

This is a piece (not by me) regarding the influence of liberal feminism in Ireland. I liked the first sentence: “A spectre is haunting Ireland, the spectre of liberal feminism. ” https://stormforcefeminist.wordpress.com/

Pingback: De Sindicatos y Prostitución. – Rebelión Feminista·

” Recognising prostitution as ‘work like any other,’ would mean, for example, that an unemployed woman worker judged to be a suitable applicant for this line of ‘work’ could be required to take up such a ‘job offer’ or forfeit her unemployment benefit.”

So… just to clarify, but I’m pretty sure this is factually untrue in NZ. There are specific laws that prevent this, and go so far as to state that if someone quits the sex trade, they are immediately eligible for Income support (as opposed to a stand down period when quitting other jobs)

You are right in saying that this is not the situation that exists in New Zealand at present. Prostitution has been legalised, but not quite recognised as ‘work like any other’ and so as far as I know it is not legally possible – at this point – to deny a woman the unemployment benefit if she refuses ‘sex work’. Informally, I would not be surprised if some suggestions, pressure, and withholding of the truth along those lines takes place in benefit interviews, but I am only guessing about that. The sentence in the article was really directed at those who campaign under the slogan ‘sex work is work like any other’ that this is the logic of their argument.