Part 8 of China in the age of American decrepitude

The overthrow of capitalism in China in the early 1950s took place under very unfavourable circumstances. From nearby Korea, US military forces threatened China with invasion and nuclear weapons; the trade blockade and associated political isolation remained serious problems. Material aid from the Soviet Union – the modern technology and capital investment needed to industrialise – would be essential for an economically backward agricultural country such as China was.

In 1941 the Soviet Union had signed a neutrality pact with Japan, in order to concentrate its forces against the German invasion in the west. (The pact also freed up Japan to concentrate its military forces against China, southeast Asia and the Pacific). From 1937 the Soviet government had aided the Guomindang – not the Chinese Communist Party – in the fight against Japan, sending guns and artillery, 900 aircraft and 82 tanks. It broke its neutrality pact with Japan in 1945 after the defeat of Germany; the Soviet Union sent 1.5 million troops into Manchuria and Korea, quickly driving out the Japanese occupiers.

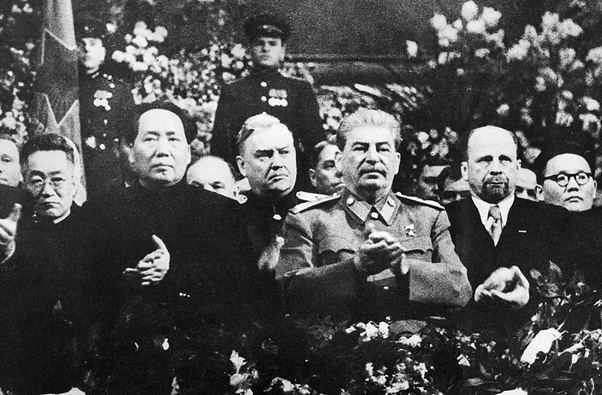

In the changed situation after Japan’s surrender, the defeat of the Guomindang and the proclamation of the People’s Republic of China, Mao visited Moscow in December 1949, and negotiated some Soviet aid. Machinery and equipment, and a few skilled engineers and other technicians began arriving from the Soviet Union. That aid provided the Soviet Union with its own best defence against the dangers of a US-dominated Guomindang regime on its own border, and later, the threat from the United States beachhead in south Korea. But as the prospect of a return of the Guomindang receded in the 1950s, the Soviet aid came to an end too. The political commonality between the two governments also broke down into rancorous mutual accusations, and later, even military clashes on their mutual borders. The Soviet leadership was attempting to solve its own problems of military encirclement by reaching an accommodation with the imperialist powers – at China’s expense. International working-class solidarity played no part whatsoever in any of Moscow’s decisions.

The only political course through which a workers’ and peasants’ government in China could tackle the problems of industrialisation and modernisation of agriculture, was through mobilising the workers and peasants, and drawing them into the discussions and decisions on industrial development. This is a complex and difficult task – even more so than the conquest of power – but there is no other basis on which progress towards socialism can be made. This course requires political leadership rather than military coercion. The only reliable ally of the Chinese workers and peasants, whose aid could be sought in this endeavour, was the working class of the world. The Mao regime, imbued with a narrow nationalistic outlook and a deep distrust and fear of mobilising the working class as an independent force, was incapable of taking this road.

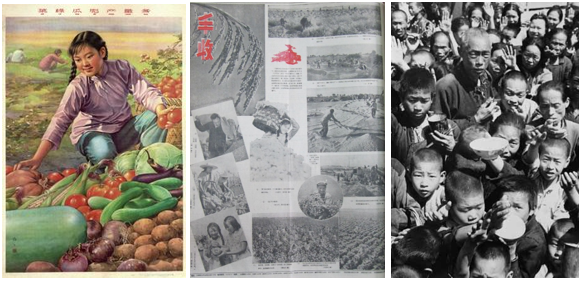

Instead, Mao lurched from a class-collaborationist policy to an ultraleft one, attempting to overcome the objective problems of economic backwardness by sheer act of bureaucratic decree. Under the slogan of “putting politics in command,” the so-called Great Leap Forward initiated in 1958 proclaimed the rapid transformation of China into a communist society. Rural labour was effectively militarised, with peasants required to eat in communal dining rooms and to sleep in barracks with the grandiose name of ‘People’s Communes.’ Daily working hours were lengthened, rest days eliminated.

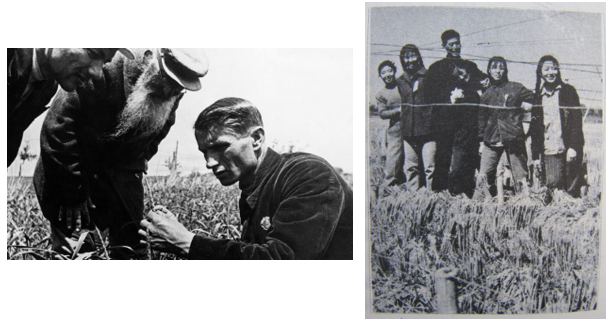

In order to squeeze more production from the land without the aid of machinery or chemical fertilisers, methods such as ‘deep ploughing’ and ‘close planting,’ borrowed from Trofim Lysenko and Terentiy Maltsev, the anti-scientific agronomists favoured by Stalin, were applied widely in China, with disastrous results. Ill-conceived pest eradication drives aimed at grain-eating birds resulted in worsening the problems of insect pests – now that the insects’ avian predators had been eradicated.

To accelerate industrialisation, a substantial section of labour on the rural ‘communes’ was directed to operate small-scale ‘backyard steel furnaces’, which were touted to ‘surpass Britain’s steel production’ within a few years. They produced little other than useless low-grade pig-iron, consumed scarce charcoal fuel – and by drawing labour away from the fields, left crops unharvested.

At the same time, the political regime became more dictatorial, with opponents of the Maoist schema within the CCP denounced as ‘rightists’ and ‘counter-revolutionaries,’ dismissed and sometimes jailed, tortured and executed. Officials fearful of falling victim to the ‘Anti-Rightist Campaign’ produced falsified reports of bumper crop yields to the leadership, leading to ever-greater demands from the central government for grain ‘surpluses’ for export.

In many respects, this was a repetition of the catastrophic forced collectivisation of Soviet agriculture in the 1930s – and with equally calamitous results. Between 1959 and 1961 famine took the lives of somewhere between 15 million and 50 million peasants, and reduced some to cannibalism. This was one of the biggest single famine events in human history. By using the hukou system – a feudal institution under which every peasant is registered in their place of birth and has strictly limited rights to move elsewhere – to block attempts by starving peasants to flee, the government was able successfully to conceal the famine from the outside world and even from most people in the urban centres. Through this process, the bureaucratic layer of government and party officials which had deformed the Chinese workers’ state from the moment of its birth, standing above and hostile to the masses of workers and peasants, became hardened and entrenched. By the same token, the foundations of the workers’ state, weak to begin with, were deeply undermined, and the very idea of communism dragged through the mud.

The Great Leap Forward was a colossal setback, not just to the peasants condemned to starvation, but also to the industry and agriculture on which the bureaucratic caste depended. Mao Zedong was left severely discredited and isolated within the ruling layer. Liu Shaoqi, at that time Chairman of the People’s Republic of China, declared that the causes of the disaster were ‘30% natural disaster, and 70% human error’ – a thinly veiled criticism of Mao – and introduced corrections that restored the functioning of capitalist market mechanisms in place of Mao’s bureaucratic schemas. Deep factional rifts thus opened within the ruling clique. In the absence of any form of workers’ democracy, these could only be resolved by violence.

At the same time, another kind of disaster was taking shape in the international plane. At the head of the independence struggle in Indonesia stood the bourgeois nationalist figure of Sukarno – the Indonesian counterpart of Chiang Kai-Shek. The millions-strong Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), the largest Communist Party in the world outside of the Soviet Union and China, took its lead from Mao and the CCP. Beijing’s advice was to look to the left-Bonapartist Sukarno for protection against the rightist generals who threatened his regime, rather than preparing to defend themselves. Just as in China itself in 1925-27, the result was the disarming of the PKI in face of the threat, and the massacre of possibly a million Indonesian workers and peasants, when the generals moved to topple Sukarno in 1965.

The Indonesian slaughter was up to that point perhaps the greatest defeat of the working class worldwide since the fascist victory in Germany in 1933. And it left China more isolated than ever before. The CCP responded with a lurch towards an ultraleft foreign policy (just as Stalin had taken a sudden shift to an ultraleft policy in the wake of the 1927 disaster in China.) Mao dusted off his old dictum about power coming out of the barrel of a gun and began aiding – in words, if little else! – guerrilla movements and armed insurgencies in various parts of the world.

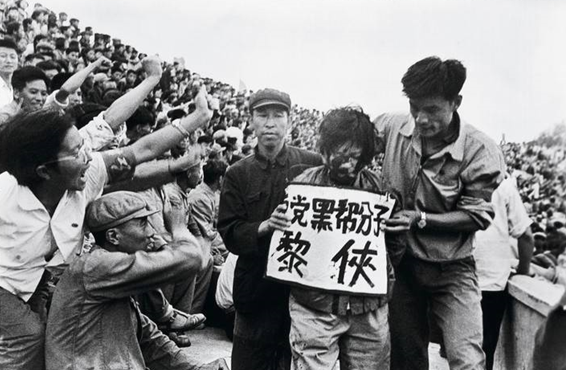

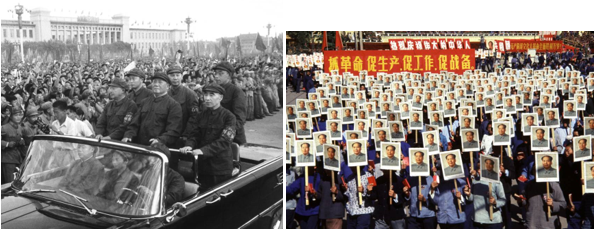

The Mao faction launched a bid to regain power at the expense of Liu Shaoqi the following year, calling on the youth to rise up against their teachers, and their parents, and to engage in violent struggle to remove ‘bourgeois elements’ that had supposedly infiltrated the government and ruling party with the aim of restoring capitalism. Mao called this the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.

From mid-1966 high schools and universities in Beijing were shut down and students were incited to denounce their teachers, many of whom were subjected to “struggle sessions” where they were humiliated and beaten, forced to confess to being ‘capitalist roaders,’ and sometimes killed. “Struggle sessions” could last weeks or months – until the accused broke down and admitted their ‘errors.’

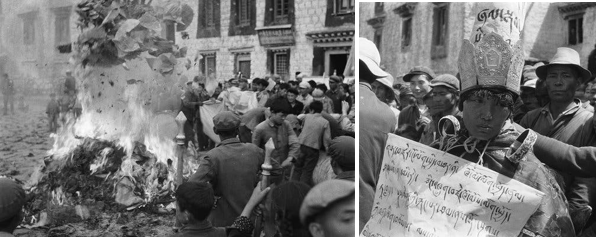

Leaders among these students were constituted as Red Guards, contingents of whom were then sent out across the country by the CCP leadership, spurred on by speeches by Mao and his chief ally, Minister of Defence Lin Biao. In the name of a campaign against the “Four Olds” – Old Ideas, Old Culture, Old Habits, and Old Customs – and with the police explicitly forbidden from standing in their way, thousands of Red Guards roamed the big cities, invading and ransacking houses (more than 100,000 houses in Beijing, 80,000 in Shanghai), evicting the occupants, burning books, looting paintings and art objects, and ransacking places of cultural and historical significance. Thousands of people were killed in Beijing alone in August 1966.

The terror escalated when it reached Guangxi province. There, tens of thousands of teachers were beaten, hundreds beaten to death or driven to suicide, thousands more permanently mutilated by the tortures, yet more thousands banished to the countryside as punishment. By the end of August 1966, across China 100,000 lives had been lost in the rampage, and half a million had been expelled to the countryside to ‘learn from the peasants.’

Among the first high-level victims was Peng Dehuai, who had been partly rehabilitated from his earlier fall from grace. He was seized by Red Guards in January 1967 and taken to Beijing, where he was paraded in chains before thousands of jeering Red Guards, wearing a conical dunce hat and a board around his neck listing his ‘crimes.’ The humiliations escalated over the following year: in August he was forced to kneel for hours before 40,000 PLA soldiers while soldiers, including Lin Biao, who had replaced him as Minister of Defence in 1959, denounced him. Peng spent the remaining seven years of his life in prison, enduring continued tortures until his health broke down and, denied medical attention, he died in 1974.

By the end of 1966, the mass organisations nationwide, including the Red Guards, were divided into two factions, one close to Mao, the other closer to Liu and the older Party officials. Mao called for “All-round civil war” to resolve the faction fight, and congratulated those Red Guards and others that had seized the local power in place of the purged officials. He also promised his faction the support of the Peoples Liberation Army.

This was a green light for military escalation of the conflict. In some parts, not just rifles but machine guns, heavy artillery and tanks were used by the PLA to suppress ‘counter-revolutionaries’ and ‘class enemies.’ Pitched battles were fought between the factions in Chongqing, Wuhan, Ningxia, and other places, with casualties in the tens of thousands. Slaughters of unarmed civilians by the PLA took place in Jianghua Yao, and many places in the Lingling district, Hunan, where 9,000 were killed in total. And the worst was yet to come.

From 1968 the violence increasingly turned inward, towards uncovering traitors and spies within the party. With its wide use of torture, conviction by forced confession, and mass terror, the Cultural Revolution approached, in both methods and scale, the Stalinist purges and show-trials of the 1930s Soviet Union. As was the case in the Soviet Union, the persecutions were so sweeping and disruptive to normal life, severe economic effects began to be felt. This led to new campaigns against ‘graft and embezzlement’ and ‘extravagance and waste,’ creating new waves of scapegoats.

The death toll in this phase, which lasted another three years, is estimated to have been between half a million and one million, with at least thirty million subjected to ‘struggle sessions’ or tortured. One of the biggest witch-hunts took place in Inner Mongolia in 1968-69 under the direction of Mao’s close collaborators Kang Sheng and Jiang Qing (Mao’s wife), where some 700,000 people, three-quarters of them Mongols, were framed and accused of being part of a fictitious separatist party, tortured and mutilated. According to an official source, some 40,000 died, and a further 140,000 were left permanently disfigured. At about the same time, Kang Sheng made a fictitious charge against a local official in Yunnan of being a Guomindang spy; the resulting ‘investigation’ led to 1.38 million people being persecuted, 17,000 killed and 61,000 permanently disfigured.

(The national and religious minorities of China – Uighurs, Huis and other Muslims, Mongols, Koreans, and Tibetans suffered disproportionately, their places of worship widely desecrated. Muslims were forced to parade in public with pigs heads tied around their necks, as part of the campaign against the Four Olds. One of the largest massacres of the later years took place in Gejiu City in Yunnan, when Hui Muslims demanded the freedom of religion guaranteed them in the Chinese constitution, and attempted to re-open their mosques. In July 1975 10,000 PLA troops were sent to put down the rebellion with guns, cannon, and aerial bombardment. Seven villages were destroyed, and 1600 Huis were killed in a week.)

Similar bloody frame-up campaigns, with their train of millions of victims, hit Shanghai, Nanning, Hebei, Liaoning, and Guilin, and later Anhui province. In Wuxuan County in rural Guangxi, it reached the depths of cannibalism – not the desperate cannibalism of starving people seen in the Great Leap Forward, but politically-motivated cannibalism, with the aim of making the whole people complicit in the crimes. The hearts, livers, genitals and flesh of the slain victims were cooked and shared out to be eaten. Some ten to twenty thousand members of the militias and mobs participated in the cannibalism – in the circumstances, who would dare refuse to partake?

The octogenarian Mao emerged from the factional carnage as unchallenged Bonapartist dictator, surrounded by the cult of ‘Mao Tse-tung thought,’ the banner of his faction. The deification of Mao reached such absurd proportions that his most banal remarks could be dutifully recorded by his sycophants and reproduced on a giant banner. Like all Bonapartist despots, he became a lonely and paranoid individual, suspicious of his closest friends – and not without reason.

The final step in the liquidation of all possible rivals to his supremacy was the elimination of his closest collaborator, Lin Biao – the Minister of Defence and Vice-Chairman of the CCP. In the course of the Cultural Revolution the military had become the ultimate authority in the country, in place of the shattered and faction-ridden CCP. This was the significance the naming of Lin Biao as Mao’s successor in 1969, by a Central Committee nearly half of which was made up of members of the army. This situation came to pose a threat to Mao himself.

Lin died in a mysterious plane crash in 1971, and was denounced as a traitor in the months following his death. Hundreds of high military officials close to him were purged. Thereby the military threat was neutralised, and the CCP, or rather, Mao’s faction, was re-established as the central organisation of the ruling clique.

The mass killings gradually subsided after 1971, although they continued on a lesser scale right up to Mao’s death in 1976, and even beyond. Hua Guofeng, who took power after Mao’s death, arrested the leaders of the Maoist faction, including his widow Jiang Qing, and officially ended the Cultural Revolution – though not the cult of Mao. Dozens more political prisoners were executed over the following year.

Just as the “Great Leap Forward” was in fact a huge leap backwards, the “Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution” was in fact both anti-proletarian and anti-culture. Education was shut down for a period of years, at the very moment when education was one of the most urgent needs of the working class.

Nor is there anything proletarian or revolutionary about smashing the cultural artefacts of the class society of the past, or desecrating places of worship, let alone persecuting workers and peasants for their religious beliefs. Marx, Lenin and other revolutionary working-class leaders always stressed the necessity for workers to open access to culture to all, and to absorb all that is useful from bourgeois culture, while discarding the rest. Far from humiliating and executing the defeated capitalists, landlords, and their well-paid servants, a revolutionary workers’ government would have made use of their knowledge and experience in the construction of socialism, as the Bolsheviks did in the early years of the Russian revolution.1

Similarly, with religion: the almighty God is a reflection of the powerlessness of the working masses before the forces of nature and society. Religious beliefs and prejudices can be overcome not by insulting the religious beliefs of the masses, but only by raising the workers’ conscious control over economic and social life. The Cultural Revolution aimed to achieve precisely the opposite of this – rendering workers and peasants compliant tools of the ruling clique. Its chief ideological product was, inevitably, a new religion: the deification of Mao, and the making of ‘Mao Tse-tung thought’ into a sacred religious scripture.

At the time these events were unfolding, the Cultural Revolution was somewhat difficult to appraise from outside of China – not least because the only sources of information about what was going on were, on the one hand, the high-sounding and self-serving lies of the Maoist faction, and on the other, the equally self-serving lies of anti-communist journalists and ‘China-watchers’ in the imperialist countries, who gleefully reported every calamity. The sheer madness of it was hard to comprehend. Even now, the scale of death and destruction in the Cultural Revolution is not easy to measure, the facts having been actively suppressed by the Chinese government at the time and ever since.

However, in the wake of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations in 1989, some Chinese historians and former officials who had gained access to the official documents of the period managed to bring some of these records to light, and today we can get a clearer picture of the upheaval than ever in the past. A handful of recollections and apologies by individuals involved in the events have appeared. The French institution Sciences Po, which aims to document such difficult-to-measure mass bloodlettings, has compiled this summary, with notes on the documentary evidence in each instance, and this has been the main source from this article.

The picture that emerges today is absolutely unequivocal: The Cultural Revolution was a blood-soaked counter-revolution, the unleashing of mass terror on a colossal scale, whose chief victims were the working class and peasantry. This ended all possibility of further advance of the Third Chinese revolution.

When the working class, in alliance with the exploited producers on the land, seizes power from the capitalists and constructs a workers’ state, it initiates a process of social transformation which cannot stand still. The revolutionary process must either move forward or fall backward. It must progress towards the construction of a socialist economy, in which the workers themselves increasingly take control of economic life through economic planning, and progressively restrict the sphere of operation of the law of value and the capitalist market in determining economic activity. If that doesn’t happen, then whatever gains the revolution has made will eventually decay, and either suddenly or gradually the capitalist market and capitalist social relations will forcefully re-assert themselves. At some point, in some form, capitalist political rule will be restored. This latter outcome is what occurred in China.

Amid the ruins and stagnation of China’s economy in the late 1970s, the task of restoration of capitalism fell to Deng Xiaoping, one of the few surviving early leaders of the CCP, who had himself been purged and rehabilitated – twice – during the Cultural Revolution. Deng’s slogan was Boluan Fanzheng, which roughly translates as ‘eliminating chaos and returning to normal’ – ‘normal’ meaning the operation of the capitalist market. Deng’s principal ally was Hu Yaobang, General Secretary of the CCP from 1982, who also promoted the rehabilitation of those persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, and supported some minor political reforms, including relaxing the repression in Tibet and Xinjiang.

In fact, Mao himself had already initiated a change of course in his last years, at least in the sphere of foreign policy: from 1971 he abruptly ditched the ultraleft rhetoric, and pursued a course of ‘peaceful co-existence’ with imperialism. He abandoned the Vietnamese fighters and others to their fate in exactly the same way China had been abandoned by the Soviet Union in the 1950s. While US bombs rained down on Vietnam, US President Nixon and Mao toasted each other in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing.

![r/HistoryPorn - Mao Zedong and Richard Nixon toasting 1976 [980 x 600]](https://preview.redd.it/to7fexo9utv61.jpg?width=960&crop=smart&auto=webp&s=c1e854b557400b5be487d66552766656bea98550)

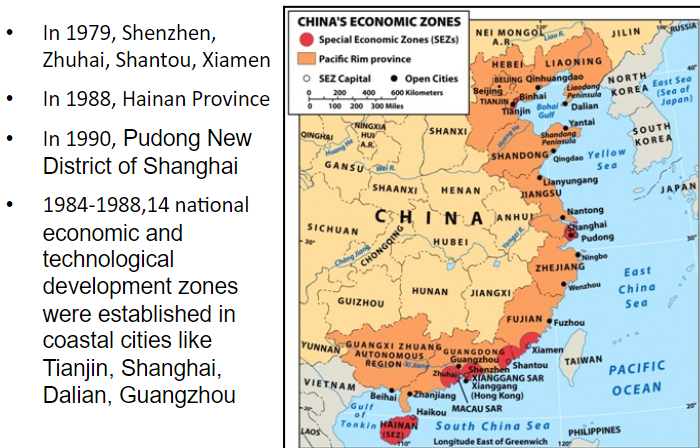

Deng merely completed the process in the late 1980s and early 1990s – privatising large sectors of the Chinese economy, beginning with the ‘household responsibility system,’ which effectively dismantled and privatised what remained of the People’s Communes. Deng’s Open Door Policy of 1978 opened the country up to investment by imperialist corporations. Special Economic Zones were set up in Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Xiamen, free of most government controls, in 1980. Soon most of these conditions were extended to 14 coastal cities. Price controls were gradually relaxed; among the consequences were inflation, and a dramatically increased degree of corruption among the ruling clique, who were well placed to take advantage of the changes. “To get rich is glorious,” Deng declared. Stock Exchanges were opened in Shanghai and Shenzhen in 1990, and growing sectors of state-owned industry were privatised (often with massively reduced wages in the privatised enterprise.)

1989 was the moment when quantity turned into quality: when the accumulation of ‘market reforms’ within the framework of the degenerated workers’ state resulted in its transformation into a capitalist state. Out of the privileged state bureaucracy emerged, through their own good fortune and massive corruption, a new capitalist class.

In April 1989 Deng’s former ally Hu Yaobang died. Hu had been forced to resign as CCP General Secretary in 1987, accused of being too soft on student protests that year; after his death, students began gathering in Tiananmen Square to mourn his passing. Soon these gatherings broadened to become demonstrations against the skyrocketing corruption, censorship and restrictions on the right to protest. The students were joined by workers, hard hit by the inflationary trends. For the first time in many years, the students formed a new organisation independent of the CCP, the Beijing Students’ Autonomous Union.

An editorial in the People’s Daily on April 26 characterised the protests as an ‘anti-Party revolt’ and a ‘planned conspiracy’ to ‘plunge the whole country into chaos and sabotage,’ and ‘negate the leadership of the CPC and the socialist system.’ This baseless attack further inflamed the protests – the demand to rescind the editorial was added to the list of grievances. In late April and early May, the protests grew to 100,000 as students defied police roadblocks and barriers to join in. The government was divided over how to respond, some supporting a military crackdown, while others favoured dialogue with the student leaders.

On May 13, students began a hunger strike which earned even wider support. Students and others poured into Beijing – up to a million on May 16-17, while similar demonstrations erupted in Shanghai and 400 other cities, including over a million in Hong Kong. An organisation called Beijing Workers’ Autonomous Union joined the protests, distributing a flier demanding to know why ‘prices had risen without respite whilst the living standards of the people had dropped precipitously.’ This was the first workers’ organisation independent of the CCP to appear in China since the crushing of the Chinese Trotskyists in the early 1950s. (Railway worker Han Dongfang stepped forward as a leader of this fledgling organisation – this interview with Han provides a vivid picture of the first awakening of an independent union movement in nearly seventy years, both its courage and its naivete.)

Deng Xiaoping asserted his authority to break the government stalemate; on May 20 he declared martial law and sent 250,000 troops to the capital. At least one military commander refused to enforce the martial law order. Tens of thousands of protestors put up roadblocks in the outer suburbs to prevent the troops entering the city, surrounding the military vehicles and appealing to the soldiers. The troops were forced to withdraw from the city and re-group.

Two weeks later, the government assembled an even larger force, and entered the city in the dead of night. Some troops entered and occupied the key buildings by stealth, dressed in civilian clothes and without weapons, which were delivered later. Once again, the main battleground was not in the Tiananmen Square itself but on the streets leading to it. Government warnings to Beijing residents to stay indoors for their own safety brought thousands out into the streets to confront the troops. This time several units used live ammunition against the protestors. Infuriated residents responded, attacking the PLA convoys with rocks and Molotov cocktails. Hundreds of trucks, tanks and armoured vehicles were destroyed, sometimes with very little resistance by the troops, sometimes after pitched battles and bloody massacres. By the time the troops succeeded in clearing Tiananmen Square, up to a thousand civilians and a handful of soldiers had been killed.

These events delivered the final coup de grace to the Chinese workers’ state, fatally weakened by the counter-revolutionary terror of the 1966-76 period. By turning its guns on the working class and youth at Tiananmen, the People’s Liberation Army made it clear to both the nation and the world that thenceforth, they served Deng’s ‘glorious rich’ and no one else. Capitalist political rule had been restored. All those who had opposed the imposition of martial law or failed to carry it out – which included Zhao Ziyang, the General Secretary of the CCP – were purged, in some cases court-martialled and jailed. Some tens of thousands were arrested in the weeks following the crackdown.

The crushing of the Tiananmen protests, the outlawing of the autonomous organisations of students and workers, the jailing and exile of their central leaders – these actions set the political stage in China for the next thirty years.

The multi-millioned working class of China, both those already in the urban industrial centres and the great reserve army of labour still in the countryside, was offered up to the capitalists, both Chinese and foreign, in an utterly atomised and defenceless state – lacking the most elementary democratic rights to organise and speak in its own name, lacking even the right of freedom of movement within China, lacking a single organisation to call its own, cut off from the rest of the world’s workers for decades, with only an embryonic sense of themselves as a class with its own separate class interests, and with the name ‘communist’ inscribed on the banner of its oppressors. These proved to be fertile conditions indeed for capitalist development.

On the other hand, the capitalist development since 1989 has vastly increased the size and economic power of the Chinese working class, and has connected it inseparably with the workers of the world. The next time class conflict on the scale of the Tiananmen conflict develops, conditions will be infinitely more favourable to the workers.

Footnote

- The Bolsheviks famously made use of these skilled servants of the old regime even in the military defence of the revolutionary republic – sometimes by persuasion, sometimes by coercive means. For the Bolshevik attitude to bourgeois culture, see, as one example among many, Lenin’s comments on the death of Tolstoy. “[The Russian proletariat] should learn to utilise at every step of their life and in their struggle the technical and social achievements of capitalism.” (Collected Works Vol 16 p327). Or where Lenin discusses the Taylor system of production efficiency, which he describes as “a combination of the refined brutality of bourgeois exploitation and a number of the greatest scientific achievements in the field of analysing mechanical motions during work.” Lenin says, “We must organise in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system and systematically try it out and adapt it to our own ends.” (The immediate tasks of the Soviet Government, 1918. CW, Vol 27, p259.)

Hi. I’ve just read this and enjoyed it a lot You might want to read the piece I have just published which develops some of your key points. https://www.blakdwarf.org/post/enter-the-dragon-the-rise-of-chinese-imperialism-and-its-nemesis

It’s a massive topic. I’m embarrassed I haven’t yet commented on your magnificent and unique series.

I’ll take this moment to toss some thoughts at you.

….

I have a few differences on the overthrow of the deformed workers state. I date it to the close of the “Cultural Revolution”, which atomized the workers state, followed by an interregnum in the 1970s as capitalist relations spread and were encouraged by the CCP.

I view Tienanmin in 1989, not as the qualitative turning point but as the expression of the established capitalist state. But in any case we agree on the general period and certainly the outcome.

….

Another point I raise for your consideration. There is no avoiding the debate whether Chinese capitalism is of a “special nature” never seen before in history.

This truly is a “state capitalism” or “command capitalism.” More importantly is the biggest single question of all. Is this form of capitalism and capitalist state, having emerged in the specific conditions and history, unique to China, “SUPERIOR” to the mercantile/finance capitalism present in all other capitalist countries, and particularly in the imperialist nations?

This has to be asked and answered as the implications are historic for capitalism and the working class of the world.

On the one hand the contrast between dotage of declining US imperialism, and all other imperialist countries and the rise of Chinese imperialism is nearly blinding.

However, setting aside a comparative analysis, there seems to be mounting evidence that this different, “special” capitalism is singularly explosive and capable of economic, social and military feats that seem unique in history. Perhaps it is because we have not witnessed anything like this since the rise of capitalism, even in the US and Japanese cases.

Some of it unfolds before us as we speak. The ability, to respond to and contain the crisis of the pandemic is absolutely astonishing and utterly unique in the world. Not only for “harsh” measures (far less harsh than in much of Europe) but to absorb and impose on capitalists the ‘necessary’ containment measures despite the pain on individual capitalists.

5,000 dead from COVID-19 in China, contrasted with 50 million Cases and 800,000 Deaths in the US alone. And worldwide 267M Cases and 5.27M Deaths. Those astonishing figures reflect a different kind of entity.

The ability to prevent the Evergreen crisis from toppling into a generalized crisis of speculative capital, unlike the U.S. with Lehman Brothers and the subprime depression, which China alleviated.

Can China ride out the cyclical crises of overproduction? We shall see. So far the rising curve of expansion and primitive accumulation has allowed China to flatten such crises to gopher hills.

The military development, and the clear trajectory to surpass the US, of China must be seen as part of its overall ‘miracle’.

There remain well less than some 300 million peasants and rural population left to proletarianize and urbanize in China, aside from the more than 400 millions already proletarianized over the past 50 years.

Once that ‘virtuous’ cycle of primitive accumulation is exhausted the miraculous spring of Chinese capitalism must be expected to have exhaust itself.

It is also true that expansionary Chinese capitalism is already bumping up against secular limits (as in the case of the energy crisis), as well as intensifying imperialist rivalries.

Another big question is –what is the Communist Party of China–? A capitalist party unique in the world and in history. A mass cadre party of 92 million. The closest in appearance in history were the two mass cadre capitalist parties of victorious fascism that oversaw petty-bourgeois bonapartist military dictatorships that acted on behalf of their capitalist ruling classes. While it would be idiotic to call the CCP a “fascist” party, there are many resemblances. More importantly what does it mean? Does it mean it is more or less stable, since it must be deeply resented by many of the biggest Chinese capitalists, as we see now, with the current campaign to rein in destabilizing speculative capitalists, and to punish any who might fare challenge the supremacy of the CCP as Jack Ma foolishly did.

……

It’s also going to be very interesting to see the development of the coming constellations of imperialist blocks. We see both sides already lining up, but this will likely make for some unexpected bedfellows.

What will German imperialism do? It seems singularly unprepared for any significant military protagonism in the foreseeable. The half-hearted attempt at a military buildup by German imperialism with the war in Afghanistan just petered out. It’s vacillation stands in marker contrast to other imperialist powers.

Perhaps the German ruling class has learned some lessons from their last two attempts. More interesting Chinese economic investment and ties to Germany are on a trajectory to significantly surpass German ties to US imperialism in the not too distant future. The railroad straight from China to Germany is transforming relations and will convert Germany into China’s warehouse in Europe, and for Africa. It is not impossible that Germany, Italy and other European powers may hitch their star to China in the coming decades.

And indeed this still has decades to unfold.

And once again the communist internationalists fit inside a few taxis.

Sorry for the overlong comment.

Pingback: How a decayed workers state transformed into monopoly capitalism in China | A communist at large·