In 1842 Friedrich Engels, the 22-year-old son of a German textile manufacturer, was sent to Manchester, England, to work in the family business. Manchester was at the time the centre of a great textile industry. Engels, who already had radical sympathies, used the opportunity to study at first hand the living and working conditions of the industrial working class, in the land where steam-power and the use of machinery for working cotton had given rise to the most advanced capitalist industry in the world. The product of Engels’ researches was published in 1845 under the title of The Condition of the Working Class in England.

This book became a classic document of working class history. Engels begins with a description of the technical basis of the industrial revolution, and how it transformed the lives of the workers. With a freshness of observation characteristic of youth – and especially of a youth newly arrived from abroad – he describes both the impressive greatness of English industry and the squalor and exploitation on which it was built. He investigates the particular conditions of workers in different branches of industry, from coal miners to textile workers to agricultural labourers, and how these conditions impact on their health and security. He explains the all-against-all competition which conditions every aspect of the workers lives. He looks at the super-exploited condition of the Irish immigrant workers. He examines the early forms of resistance by the workers to their exploitation.

In other words, The Condition of the Working Class in England is a great deal more than simple description and reporting. It is a critique of capitalist society and a perspective for the transformation of that society by the working class, written by a young revolutionary fighter who had already developed a materialist socialist outlook.

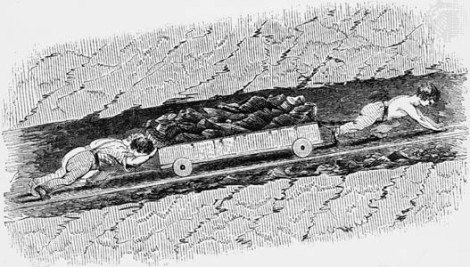

Yet for all that, it is still the direct reporting of the living and working conditions of working class at that period of history which most commands our attention today: the stories of coal mines where children as young as four or five years old worked underground for 12 hours a day, the descriptions of the foul air of disgusting overcrowded sleeping barracks, the shortened life-span of the knife-grinders of Sheffield, whose conditions of work were so injurious to their health that the alcoholics among the workers usually lived the longest, simply because they were more frequently absent from work. (The grinders who worked on wet stones usually lived to about 40 to 50, while those who worked on dry stones died at between 28 and 32 years of age.)

Conditions similar to these developed in the other countries of Europe and America as industrial capitalism spread to these countries. Yet almost nowhere – unfortunately – was it ever described in such a thorough and penetrating way as it was in England by the young Engels. The lives of those whose labour built the modern world went almost totally unrecorded, unwritten, unnoticed, and quickly forgotten by bourgeois society after their premature deaths. It remains that way today.

The handful of exceptions to this rule, therefore, take on an immense importance – such as the accounts written by slaves from the cotton plantations of the southern United States who escaped to the North, accounts that were published as part of the campaign to abolish slavery.

A unique document of this kind also appears in the history of the working class in New Zealand, and thanks to digitisation of archives, is now easily available to read in the original, for the first time in over a hundred years.

In the late 1880s, true capitalist relations of production had only just developed in New Zealand. Easy access to the land – what Engels calls ‘the great safety valve against the formation of a permanent proletarian class” [1] – had closed off. A deepening depression in the late 1880s had revealed the existence of an “industrial reserve army, available at the times when industry is working at high pressure, to be cast out upon the street when the inevitable crash comes, a constant dead weight upon the limbs of the working-class in its struggle for existence with capital, a regulator for keeping of wages down to the low level that suits the interests of capital…[and] the overwork of some [became] the preliminary condition for the idleness of others” [2]

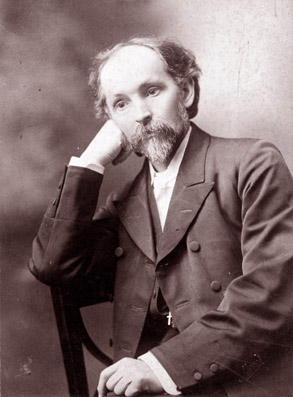

Rutherford Waddell

Photo: http://www.archives.presbyterian.org.nz/photogallery17/page1.htm Ref : P-S15-22

The distress that resulted from the depression led to a public outcry. A Dunedin minister of the Presbyterian Church, Rutherford Waddell, began sermonising against workers having to work in overcrowded and insanitary workshops, for long and irregular hours, and for low wages – what was termed ‘sweated labour.’ The Otago Daily Times, Dunedin’s main newspaper, assigned the reporter Silas Spragg to investigate, and his revelations added further fuel to the fire.

The government felt compelled in 1890 to set up a Royal Commission to investigate. Set up along similar lines to a Commission in Britain around the same time, it became known as the Sweating Commission. It held hearings in the four largest cities, hearing testimony from factory inspectors, doctors, union leaders, journalists, manufacturers, and many workers, especially workers in the clothing industries, but also tramways workers, bakers, saddlers, millwrights, shop workers, and hairdressers. Many workers testified only on condition of anonymity, for fear of victimisation by their employers.

Waddell was appointed to the Commission, and Spragg testified before it. The 114-page report of the Commission [3] records all this testimony verbatim. The report naturally lacks the careful structure and insights of Engels’ book, but it nonetheless provides a fascinating snapshot of the working class in New Zealand at this pivotal point in its history – in many cases, in the workers’ own words.

The Commission found [4] that in some cases wages were now even lower in New Zealand than in Britain. It noted cases of bakers who earned a wage of 25 shillings plus meals for a week of 108 to 112 hours. Adult men had been increasingly replaced in the factories by the cheaper labour of women and children, at very low wages. Girls were found to be working an 18-hour day for 7 or 8 shillings a week. Shop assistants and waitresses in restaurants earned 10 shillings to 12 shillings for a 90-hour week. Uncounted hours were added to the working day, especially of women, by the widespread practice of taking sewing work home, to be paid on piece rates.

[In the Imperial currency of the time, 12 pence (12d) = 1 shilling (1s) and 20 shillings (20s) = 1 pound (£1). “I do not think a single woman living in lodgings could live on less than 10s. or 15s. a week, and 5s. a week would not more than keep her in clothes and boots,” one worker estimated.]

“In the trades especially in which young women are employed, such as millinery and dressmaking, it is not unusual for young girls to give their services for the first year for nothing, and the second year for 6s. a week. At the end of that time, if they ask for an increase of wages, they are, in many instances, discharged, and other young girls are taken on in their places,” the Commission reported.

Many workers testified about low and declining wages, often with further deductions made for ‘breakages’ such as broken needles in a sewing machine. This was especially true for workers on piece rates. “Some girls took the work home—that is, to sew the toes. They received 2s. a dozen for sewing the toes. That was the average rate in the town at that time. The rate of wages was higher at the beginning : first it was 2s. 3d. a dozen, then 2s., then 1s. 9d., and when I left it was 1s. 6d,” a stocking-knitter testified.

Factory law required that the factory be shut during meal times, but often there was no provision for any alternative accommodation made, so that workers were made to stand outside during their meal breaks. Workers testified about health problems resulting from long hours bent over a machine.

During this time, many workers were beginning to organise in unions, and some testified to the victimisation they suffered as a result. “Mr. Moore heard I was on the committee of the Union, and he dismissed me. He said to me, “If you take my advice you will leave the Union, and not bother with it.” I said, ” No, Mr. Moore ; I have joined the Union, and am not going to leave it.” He said, “I am going to put up a log of my own, and if those who belong to the Union do not leave it before Saturday I will turn them out.” He told me there was no wool for me, and he paid me off. I believe that another hand was dismissed for the same reason.” (A log was the name for a schedule of claims regarding pay and conditions that the union demanded).

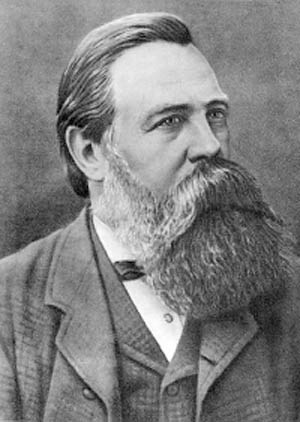

John Andrew Millar. General Assembly Library :Parliamentary portraits. Ref: 35mm-00162-b-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22808439

John Millar, a ships officer and general secretary of the Seamen’s Union, testified before the Commission. “There is now no chance of a man saving enough to buy land and to put his boy on it,” Millar said, “and the only prospect the boy has is 15 shillings a week for his food for the rest of his lifetime…I think one of the principal questions is the question of boy-labour throughout the colony…The majority of businesses and trades are overrun with boys; in fact, in New Zealand the proportion of boys employed is larger than in any other of the Australasian Colonies…I complain of the employment of boys because of its effect upon the wages of the workmen: it does away with the employment of the legitimate breadwinner of the family—the father.”

The widespread practice of employing boys, girls and women at low wages in place of skilled adult male workers had undermined what little power there was in the existing trades unions, which depended on regulating the supply of those skills. A new kind of union was required, one which incorporated the young, the unskilled and the female workers, and which included all the workers in an industry, rather than just the skilled crafts. Exactly that kind of union began to appear.

From the middle 1880s there was a series of strikes among waterside workers at all the main ports, and among coal miners at Kaitangata and on the West Coast, for union recognition. These were strikes aimed at forcing the employers to hire only union members. Although most of these ended in defeat [5], new unions were continually formed and existing ones underwent rapid growth. Strikes in solidarity with other local unions developed: when Dunedin waterside labourers struck, others at Lyttelton and Wellington went out in sympathy. Waterside workers raised funds to support workers on the other side of the world, during the London Dock Workers Strike of 1890.

In 1888 it is estimated that there were 3,000 trade union members; by mid-1890, they claimed 60,000 [6], (at a time when the total population of the colony was still only 600,000) and their numbers were still growing. Unions began to organise beyond the skilled trades, and to include women workers for the first time. Unskilled labourers in Canterbury formed a union, including the unemployed workers in their ranks. Unions of tailoresses, waitresses and domestic servants were formed. Rural workers organised. The shearers union organised many Maori shearers. In 1886 it had translated its rules into te reo Maori in order to win their support.

Union organising began to yield real gains for the workers. Ellen Wilson, a shirt finisher, testified before the Sweating Commission: “Sixteen months since it was hardly possible to earn a living. The best week I had then, working hard, was 10 shillings. That was working from 9 in the morning till 11 at night, with no hours off for meals… I can now make 12 shillings or 13 shillings a week, working eight hours per day… The Union has been a great boon to us. I would not for anything it was dissolved, because it has done away with taking work home at night.”

The most important new federation of unions that developed out of this ferment was the Maritime Council, which brought together the key unions of seafarers, wharf labourers, miners and railway workers, both in New Zealand and Australia, organised by whole industry rather than by craft. This was the first national union federation in New Zealand, and at its height it brought together 22,000 workers [7]. The leading figure in the Maritime Council was John Millar. He declared himself for the ‘new unionism,’ and against ‘the mixing up of trade and friendly society affairs.’ [8] On the first anniversary of the Maritime Council on October 28, 1890 he organised a demonstration in support of the 8-hour day.

The capitalists on both sides of the Tasman could not tolerate a workers organisation with such potential power, and they resolved to crush it. A dispute was provoked in Australia and deliberately spread to New Zealand. In August 1890 the Maritime Council in New Zealand called a strike of seafarers in solidarity with its Australian counterpart in protest against the use of non-union labour to load a ship in Sydney, and the other unions affiliated to the Council also joined. Coal miners refused to supply the scab-loaded ships with coal. The Tailoresses and other unions declared their support for the Maritime Council.

The bosses responded quickly to these actions. Railway workers at Lyttelton who refused the order to handle the goods from the scab ships were sacked. Employers in Christchurch organised a labour bureau to recruit strike-breakers from among bank clerks, school teachers and farmers to work the wharves, and within two weeks they were able to re-open the ports. Across the Tasman, armed troops were deployed to protect strike-breakers at the ports of Sydney and Melbourne and elsewhere.

The newly-formed unions had little resources and experience to build on; within six weeks, the shipping company had their steamers running again and the Railways their train services. In November the Maritime Council declared the strike off.

Unionists on the wharves wanting to return to work found their jobs taken permanently by strike-breakers and their organisations destroyed and replaced by employer-led scab operations. While the Seamen’s union managed to maintain a reduced existence in some ports, the unions of coal miners and wharf labourers were smashed, and were not able to re-form for several years.

The Maritime Strike of 1890 was a seminal event. It marked the birth of a self-conscious working class in New Zealand. The strike, the upsurge of union-organising it that preceded it, and its outcome determined the course of the labour movement for almost the next two decades.

Second in a series of three articles on the working class in New Zealand up to 1900

Next article: The sheltered childhood of the working class in New Zealand

Notes

- Engels, Preface to the 1886 American edition of Condition of the working class in England.

- Engels, Socialism Utopian and Scientific

- Report of the Sweating Commission, Appendix to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1890 session, New Zealand.

- Sutch, W.B. The quest for security in New Zealand, Oxford University Press 1966, p66.

- Salmond, J.D. New Zealand Labour’s Pioneering Days, Forward Press, 1950, p76-77

- Roth, Herbert, and Hammond, Janny. Toil and Trouble, The struggle for a better life in New Zealand, Methuen 1981. p34

- Salmond, J.D. op cit p87

- ibid, p81

Pingback: The sheltered childhood of the working class in New Zealand: 1890-1912 | A communist at large·

Pingback: Capitalist farmers and family farmers | A communist at large·

Pingback: Why the founding of the Labour Party was a historic advance | A communist at large·